MirrorMoon EP, Santa Ragione

The second volume of the Triennale Game Collection, curated by Pietro Righi Riva, is being launched on the occasion of the 23rd Triennale Milano International Exhibition. Matteo Lupetti introduces videogames and the authors featured in the collection.

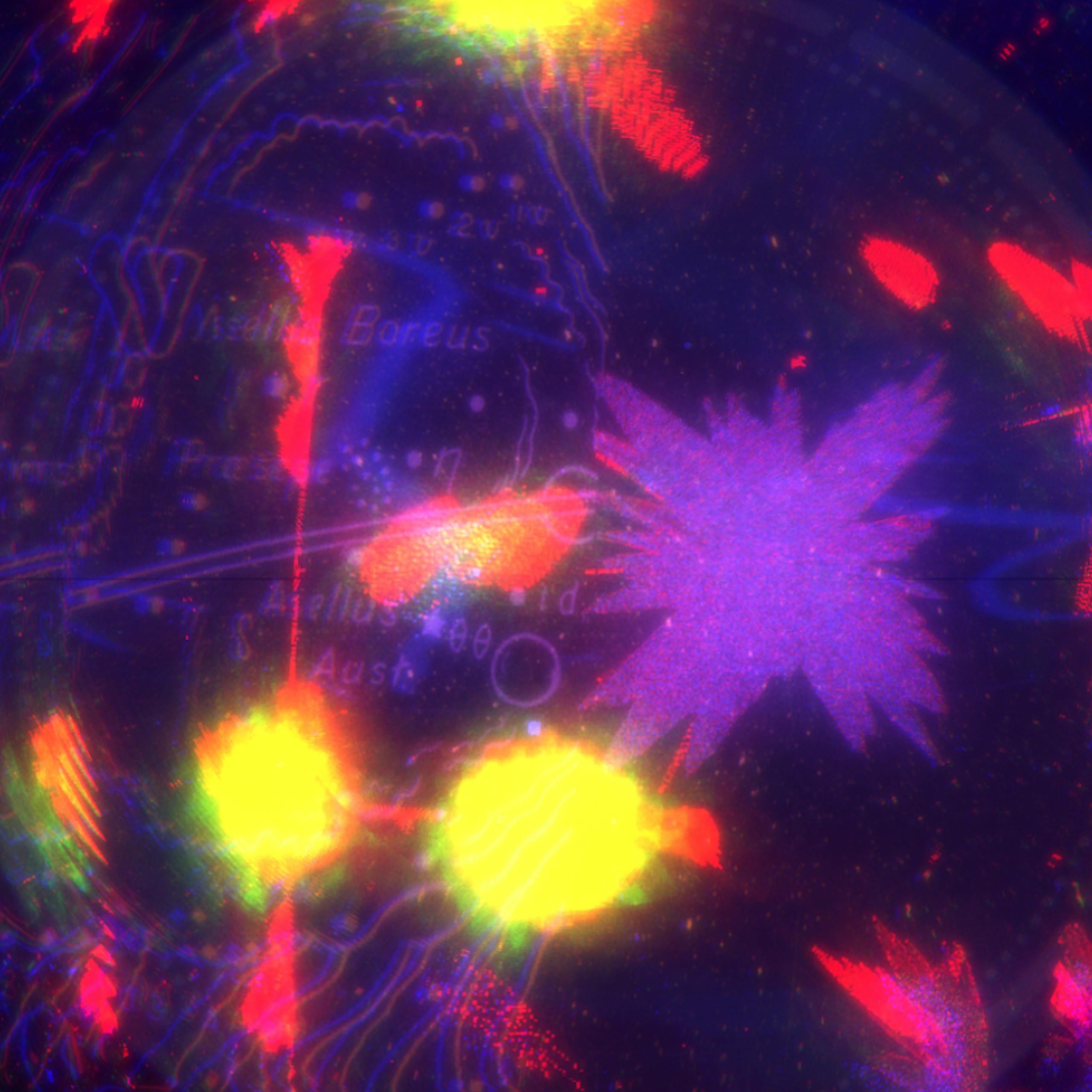

At the beginning of the videogame MirrorMoon EP by Santa Ragione (2013), we are in the cockpit of a spaceship before a myriad of keys, screens, knobs and levers whose function we do not know. We activate switches, a bit randomly, push a button, and suddenly we find ourselves on a planet. We are holding something that seems like a gun but it doesn’t shoot. There’s a moon in the sky, and at a certain point, we realize that it is actually a copy of the celestial body on which we stand, in effect, a three-dimensional map suspended above us. We walk on the planet, finding architectural structures and adding pieces to our strange gun. Now we can interact with the moon, turning and moving it. Maybe we even begin to understand something of this mysterious world.

For the 21st International Exhibition Triennale Game Collection in 2016, the director of Santa Ragione, Pietro Righi Riva, curated a selection of videogames commissioned specifically to address the themes of the exhibition in that medium. Now, in 2022, a second volume will be released, conceived for the 23rd International Exhibition entitled Unknown Unknowns. An Introduction to Mysteries. In fact, videogames have much to tell about how we relate to the unknown because when we enter the world of a videogame, like that of MirrorMoon EP, we inevitably enter an alien space whose rules we do not know, especially at first, a space that we only understand insofar as it reminds us of the actual physical space.

Mirror Moon Ep, Santa Ragione

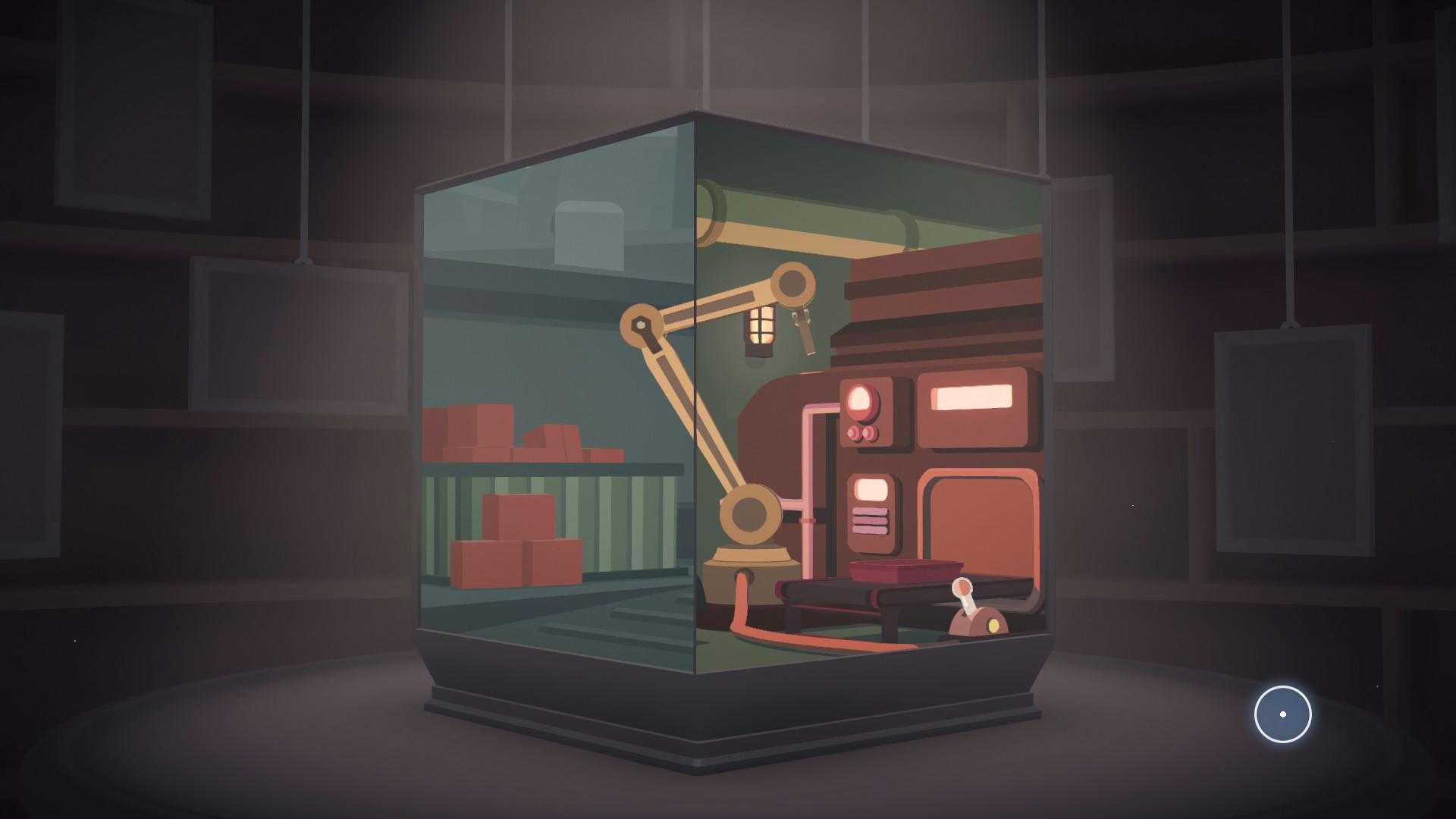

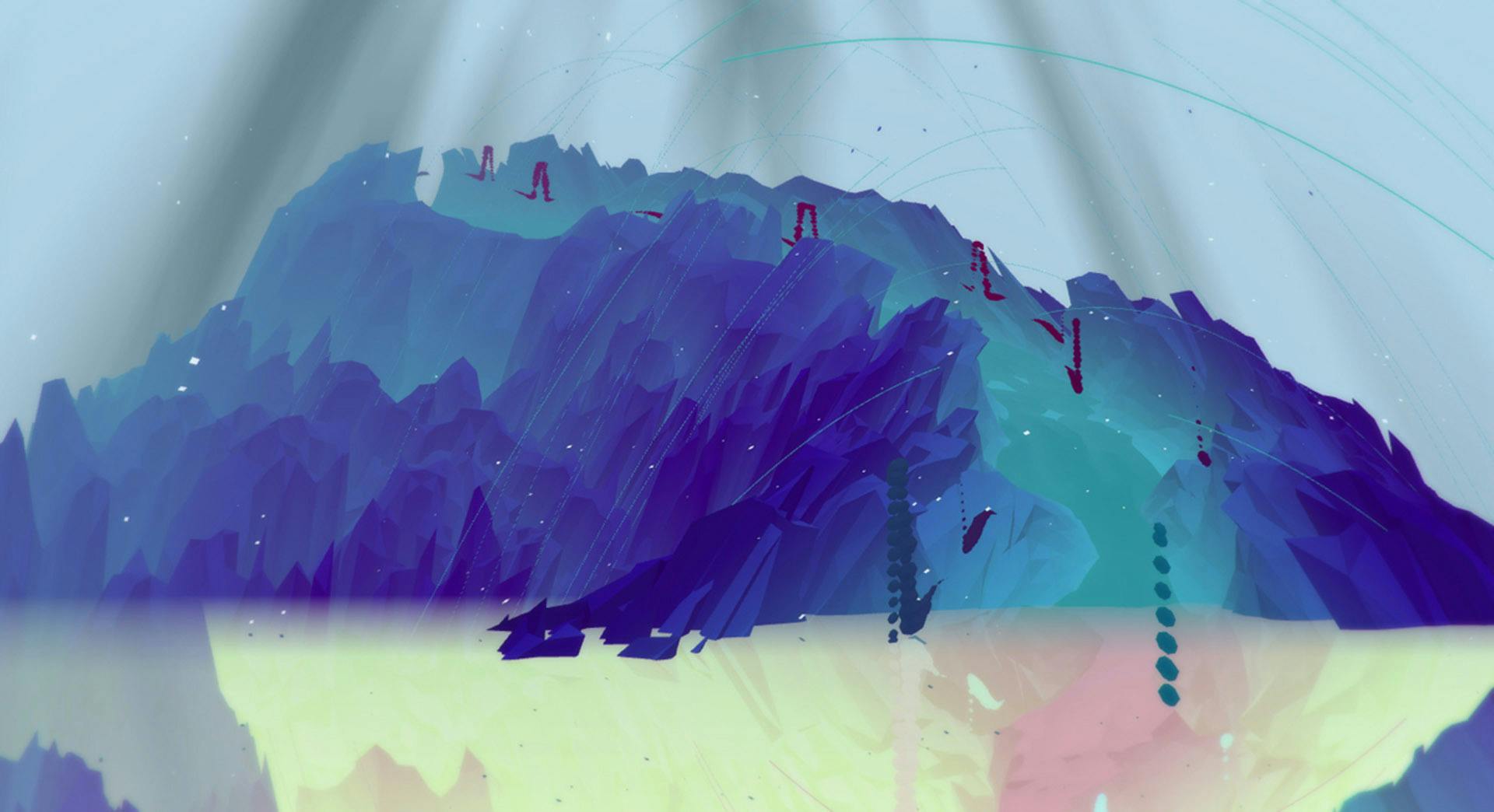

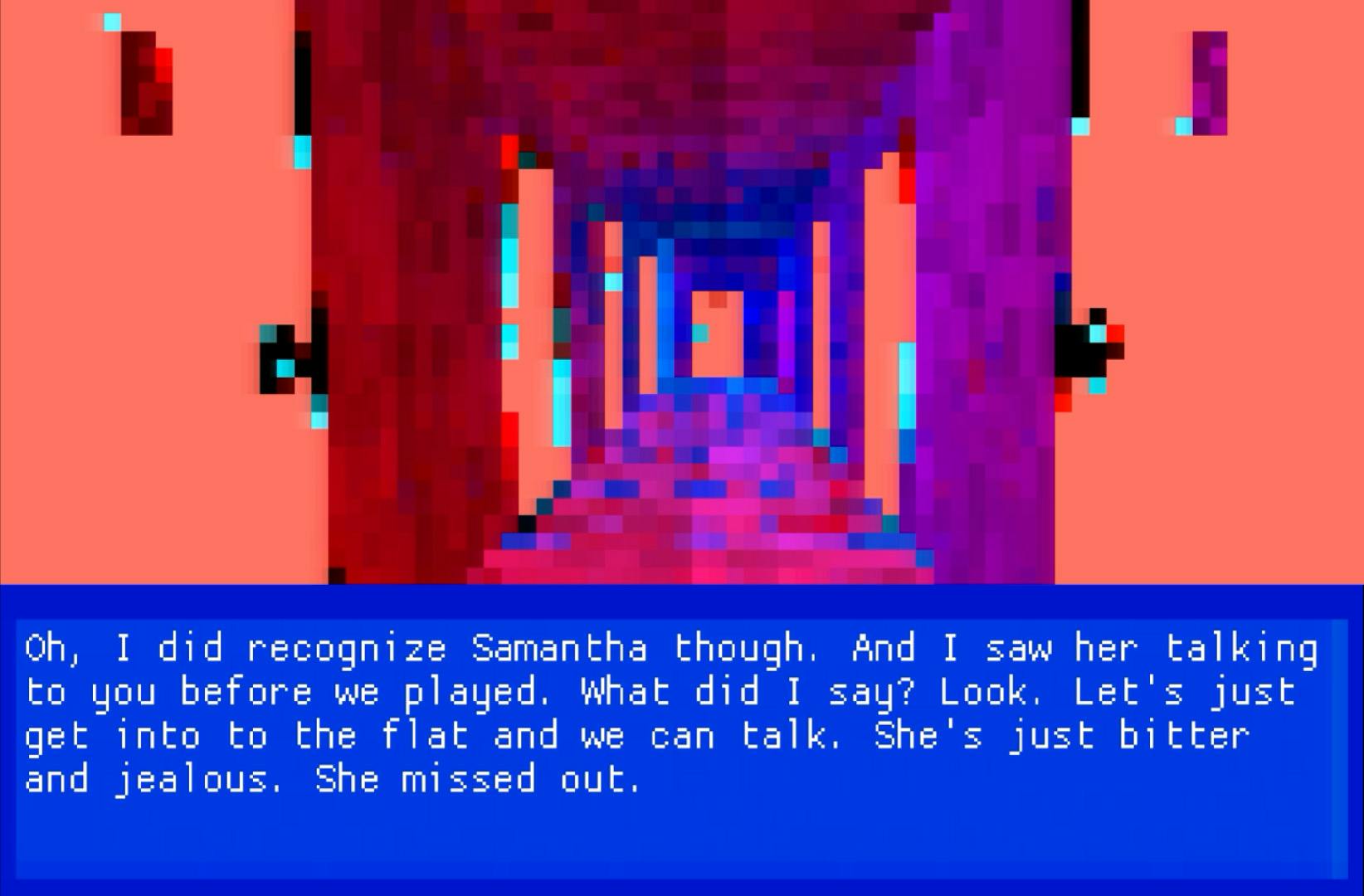

The central role played by the videogame space is seen clearly in the earlier works of a number of the authors featured in the second volume of the Triennale Game Collection. These include perspectives that become puzzles to be solved in Moncage by Optillusion and XD (Optillusion has created another puzzle, WADE, for this Triennale Game Collection), landscapes that change when the music is manipulated in Panoramical by Fern Goldfarb-Ramallo, David Kanaga and Finji (Goldfarb-Ramallo presents the audiovisual work We are Poems in the second Triennale Game Collection) or the domestic space—made alienating by the abuse that has taken place there—in Last Call by Star Maid Games (Nina Freeman, whose Nonno’s Legend will be featured in the Triennale Game Collection) and in Curtain by Dreamfeel (Llaura McGee, whose Contact will appear in the new Triennale Game Collection).

Panoramical, Fern Goldfarb-Ramallo, David Kanaga e Finji

Last Call, Star Maid Games (Nina Freeman)

Michel de Certeau, in L'Invention du quotidien 1. Arts de faire (1980), wrote, “Every story is a travel story, a spatial practice,” (The Practice of Everyday Life, University of California Press, 1984). Henry Jenkins called the development of videogames “narrative architecture” and wrote, “Game designers don’t simply tell stories; they design worlds and sculpt spaces.” (“Game Design as Narrative Architecture” in First Person. New Media as Story, Performance, and Game, MIT Press, 2004).

The history of the creation of videogames begins with table games and paper role-playing games, like Dungeons & Dragons, where the space in which the action takes place is crucial, be it the gameboard, the dashboard or a subterranean labyrinth (the dungeon). Most of all, the first textual videogames offer a description of their places. “You are standing at the end of a road before a small brick building. A small stream flows out of the building and down a gully to the south,” begins Colossal Cave Adventure by Will Crowther and Don Woods (1977), forefather of the “adventure” genre that takes its name from this game and inspired series such as Monkey Island.

At a time when cities are growing to occupy the entire Earth and space seems to be the exclusive prerogative of Elon Musk for the moment, videogames offer new frontiers to explore in a world that, for a very specific segment of the human population, seems limitless. “The description and analysis of virtual technologies as the opening up of a new frontier, a movement from known to unknown space, responds to our contemporary sense of America as oversettled, overly familiar and overpopulated,” Jenkins stated in a conversation with Mary Fuller, expert in trade, exploration and colonization in the early modern era. (“Nintendo® and New World Travel Writing: A Dialogue” in Cybersociety: Computer-Mediated Communication and Community, SAGE Publications, 1995).

Exploration of the new videogame frontier is often violent. Players conquer space, robbing it of its treasures and massacring its previous inhabitants. Aliens are enemies and territory is a resource to be exploited. In fact, the space in these videogames is explicitly designed to be conquered. The conquest of videogame space is the players’ “manifest destiny” just as the expansion from one end to the other of the continent was, according to the widespread belief of the 19th century, the “manifest destiny”, the justified mission, of the United States of America.

“I would speculate that part of the drive behind the rhetoric of virtual reality as a New World or new frontier is the desire to recreate the Renaissance encounter with America without guilt,” added Fuller in the same conversation with Jenkins. “This time, if there are others present, they really won’t be human (in the case of Nintendo characters), or if they are, they will be other players like ourselves, whose bodies are not jeopardized by the virtual weapons we wield.” Fuller doubted, however, that the new digital frontier was actually without victims, and from another perspective, MINE by Akwasi Bediako Afrane, part of the second volume of the Triennale Game Collection, shows the human and environmental cost of the creation of the digital devices we use every day.

In fact, many videogame genres revolve specifically around the violent conquest of territory. Some videogames are based on strategy, such as Civilization and Age of Empires, discussed by Souvik Mukherjee in his Videogames and Postcolonialism. Empire Plays Back (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017). Then there are the so-called “metroidvania” (portmanteau of the two main games in the genre, the Metroid and Castlevania series), that is, the videogames defined by Chris Totten in the first edition of An Architectural Approach to Level Design (A K Peters/CRC Press, 2014) as “reward-possibility mazes”. As Totten explained to us in an email, “They are games that put players in a large consistent environment where the goal is to escape. This is accomplished by exploring the maze and finding permanent upgrades (rewards) that increase the movement and/or offensive capabilities of the player avatar, which in game studies terms is called ‘increasing the possibility space’.” Nonetheless, there are alternatives to this way of relating the encounter with otherness.

“Metroidvanias tend to be largely power fantasy,” wrote James Primate, composer and designer of the levels of the videogame Rain World by Videocult and Akupara Games (2017), a game in which we interpret a part-cat-part-slug creature in a brutal post-apocalyptic world. “By far my favorite part of Metroid type games is the early beginning, where you quietly explore strange alien worlds, intensely observing your surroundings for clues to how these worlds work, sneaking around afraid of anything that moves as you are still quite fragile at that state. We wanted to make an entire game from that feeling. We wanted to reward observation, and understanding. There is no material or power progression in Rain World, there is only the knowledge you take from exploring and experimenting.”

Rain World, Videocult e Akupara Games

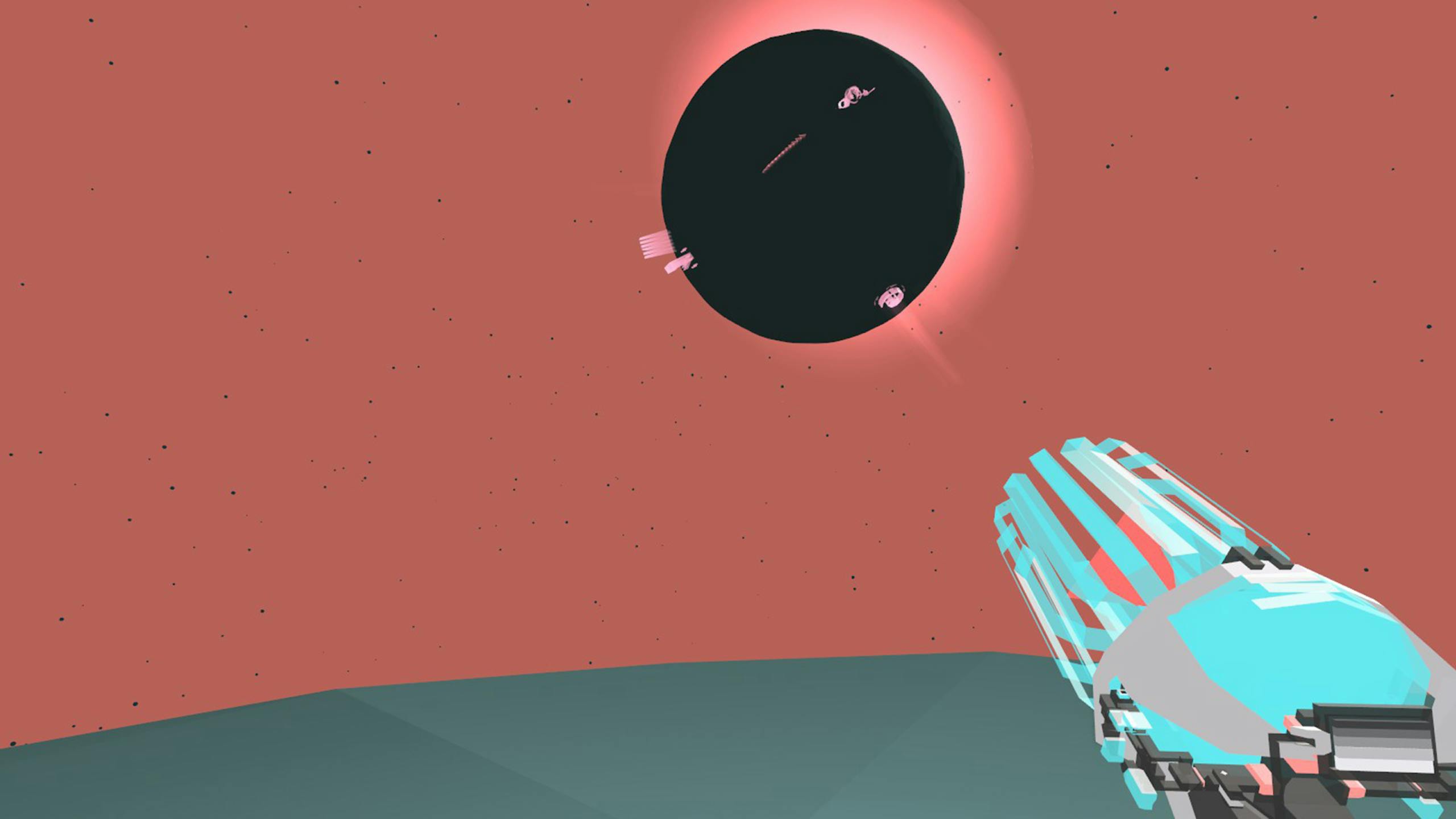

In Outer Wilds by Mobius Digital and Annapurna Interactive (2019), we freely explore a solar system in search of the secrets of its past, without objects or abilities to acquire and without fighting. As the developers of Mobius Digital told us, “The player’s motivation for exploring had to be that the player wanted to know more about the world. This leads to removing any sort of extrinsic rewards like upgrades or leveling up. The only reward had to be knowledge. [...] Instead of conquering these systems, players must explore space to gain the knowledge needed to understand them.”

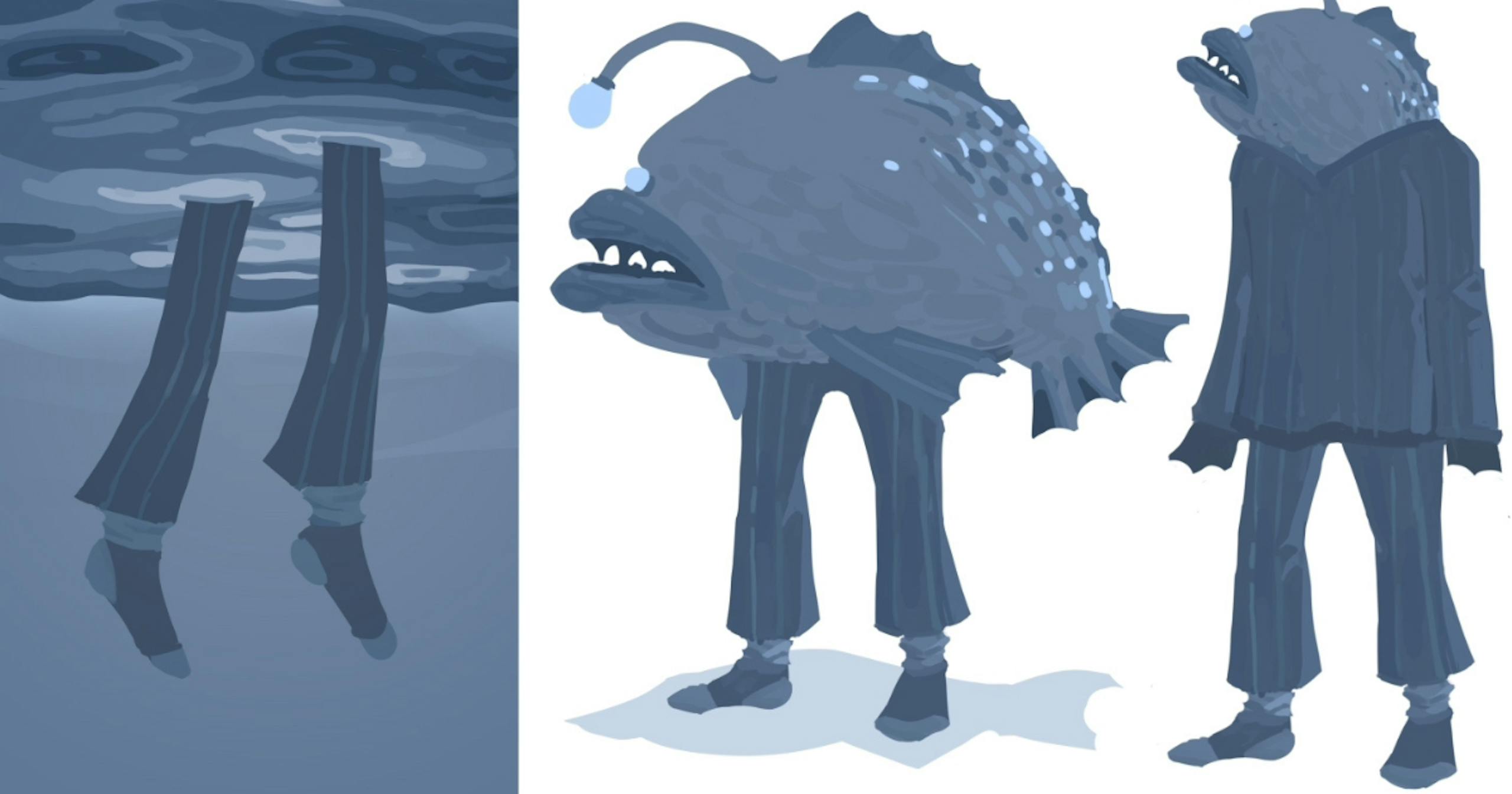

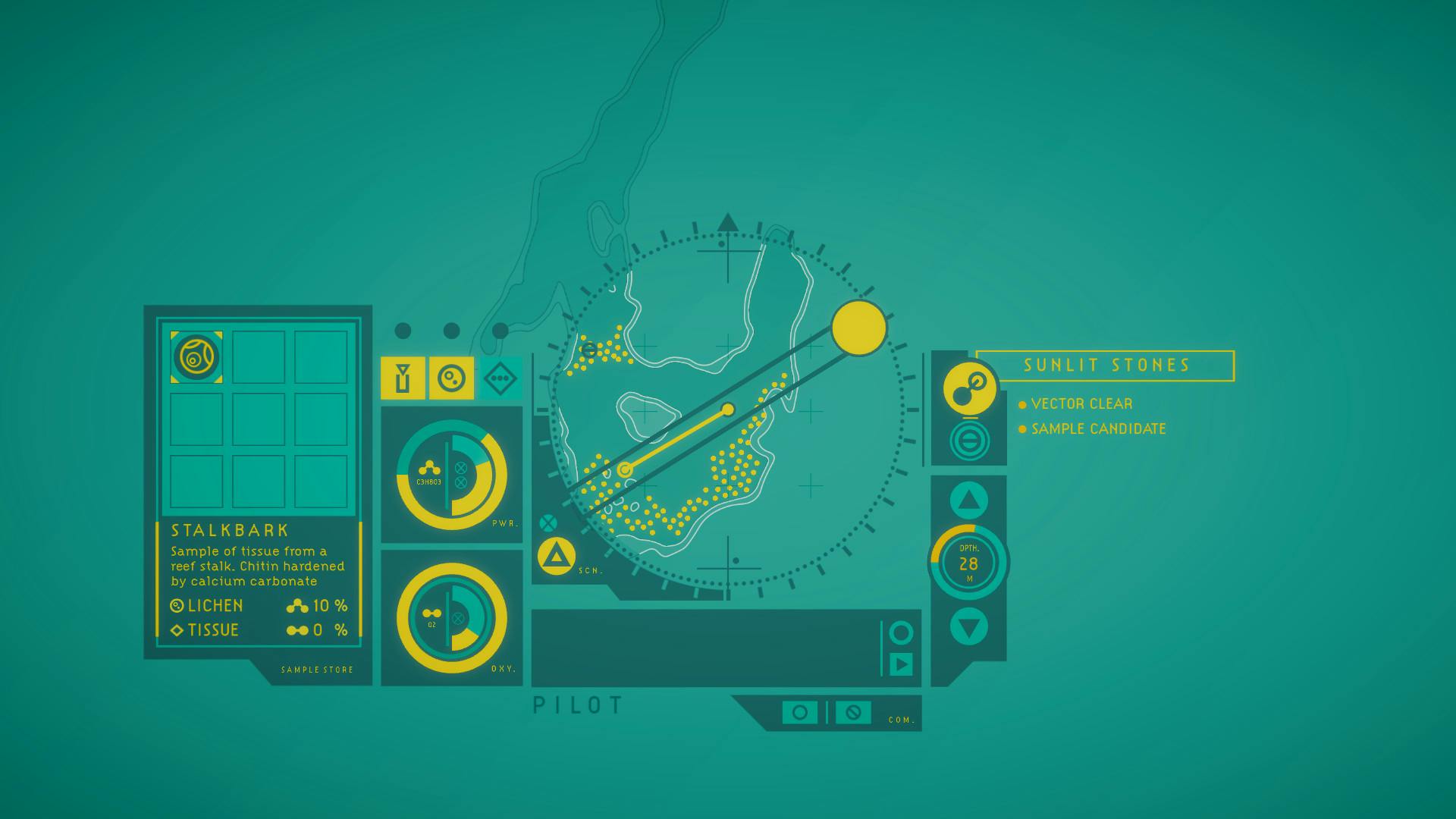

In 2020, Gareth Damian Martin (Jump Over the Age), curator of Heterotopias, a digital magazine focusing on the relationship between videogames and architectural spaces, published In Other Waters with the publisher Fellow Traveller. The game is set in the depths of an alien ocean, but we have to understand this world before we can move in it. In an email to us, Damian Martin explained, “In Other Waters is an attempt to make a game where players engage with the ecosystem of an alien planet, rather than just treat it like a backdrop. [...] These are not violent interactions, and they don't change the environment permanently, instead they engage with it, communicate and work with it on its own terms. [...] The whole game is built around the idea of re-configuring our relationship to ecology both in the game's narrative and its mechanics. I hope it can also affect player's relationships to ecology in their lives too, and maybe help them to understand there are other ways of thinking about our relationship to our planet and the other life which occupies it.”

Curtain, Dreamfeel (Llaura McGee)

If the videogame space is an alien one, then analyzing and rethinking the medium can help us understand how we see—and how we might see—our relationship with the unknown, with what is other than us and which we do not yet understand and perhaps will never fully understand. “Games are a site where real spaces are represented, contested and inverted all at the same time,” Martin concluded, “and so they reflect back onto our understanding of space, both virtual and real.”

In Other Waters, Jump Over the Age e Fellow Traveller