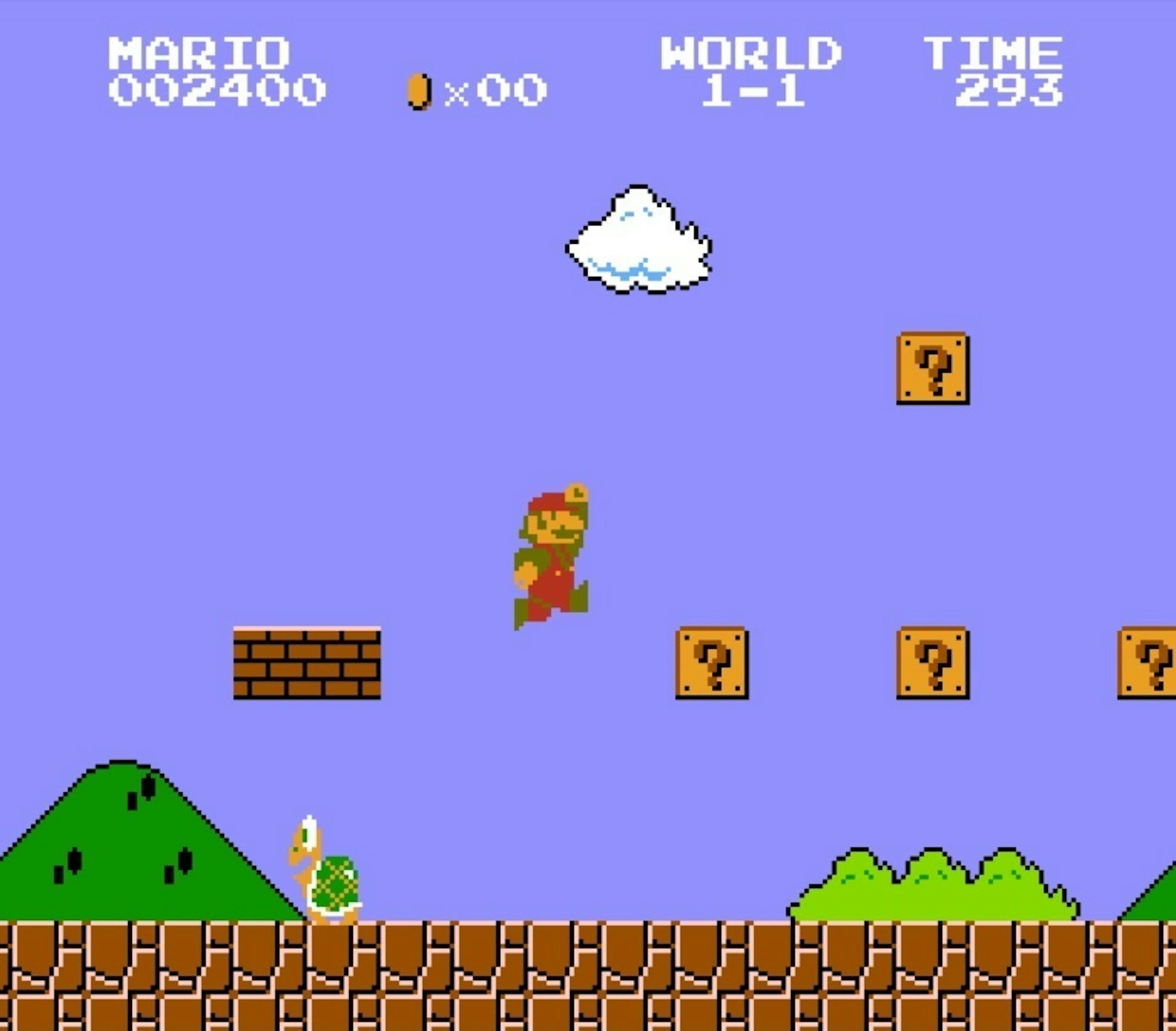

Super Mario Bros, Nintendo, 1985

The term “video game” stresses the visual aspect of digital play, but the audio elements are just as much a part of the medium as the visuals, with the players becoming the actors, the performers, on a visual stage made up of both sights and sounds.

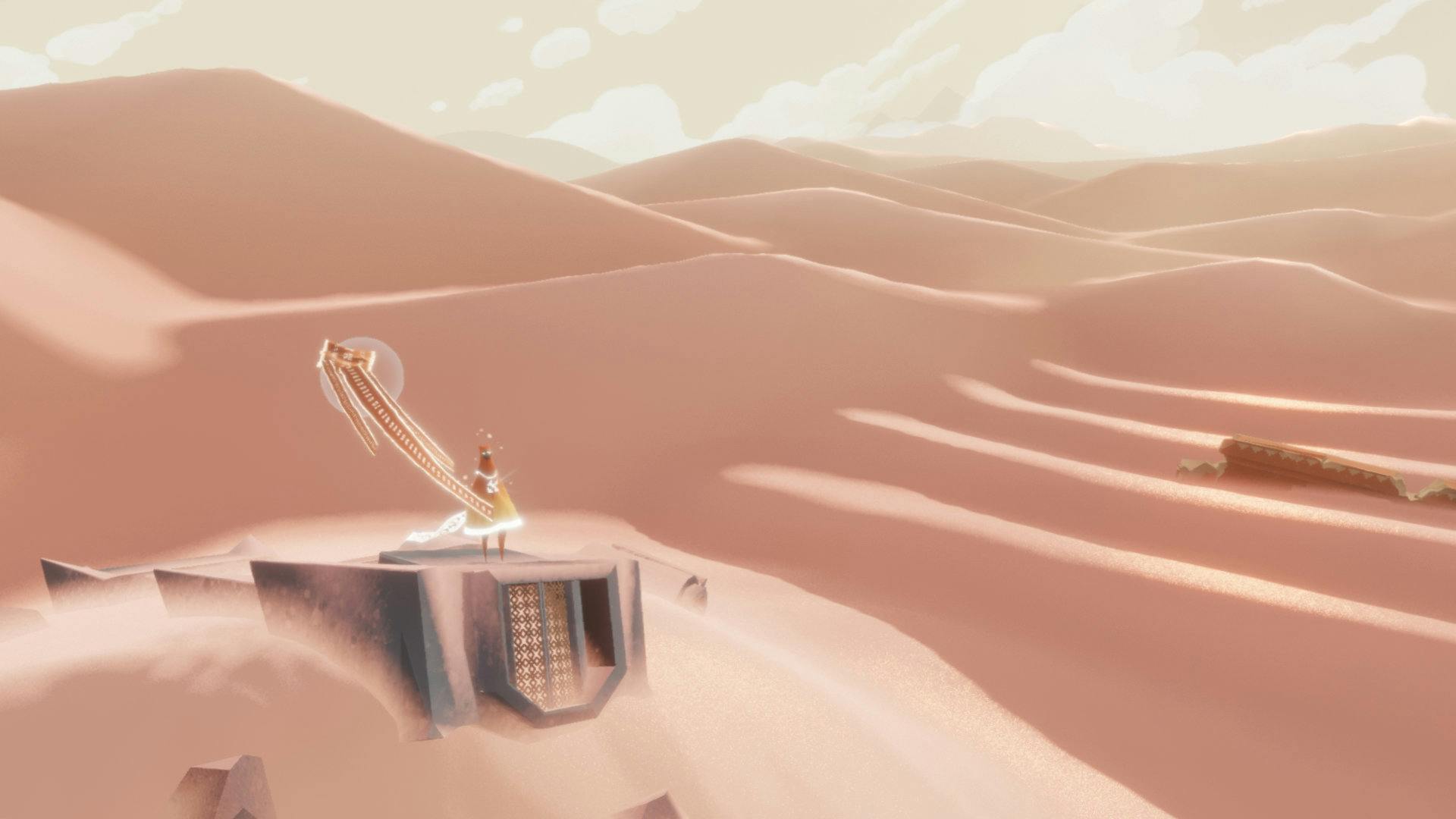

Each video game has its distinctive sound, from the four lone notes played at an increasingly brisk tempo to usher in the alien threat of Space Invaders (Taito, 1978) to the almost orchestral music composed by Austin Wintory for Journey (Thatgamecompany, Sony Computer Entertainment, 2012), during which the cello narrates the main character’s journey through the different visual and musical settings. As a rule, these soundtracks are extra-diegetic (meaning that the music is not heard in the fictional world), like those that accompany the narration and rhythm of films. But in the final analysis, the sounds are tied to the settings, or at the very least they summarise or render them in abstract form. In Super Mario Bros. (Nintendo, 1985), the levels found out in the open have a different type of music than settings such as dark caves, the depths of the sea or castles of stone, fire or lava.

Journey (Thatgamecompany, Sony Computer Entertainment, Annapurna Interactive, 2012), immagine via Steam

The jumping in Super Mario Bros. also has a sound of its own, as do the coins that get collected, with every action seemingly producing a distinctive musical footnote. This technique is taken from the film industry, in which the term “Mickey-Mousing” refers to the way the music follows and comments on movements and actions. A similar approach had already been employed by Richard Wagner, through the use of leitmotivs, or recurring musical themes that represent characters, places, objects or concepts.

Proteus (Ed Key, David Kanaga, Twisted Tree, 2013) immagine via Steam

Max Steiner, who established the sound of Hollywood productions with his scores for more than three hundred films, including Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939), relied heavily on the Wagnerian leitmotiv, which has been passed on to video games as well, as shown by the soundtracks that Nobuo Uematsu composed for the Japanese series Final Fantasy by Square Enix. Ultimately, this is the outcome of Wagner’s overriding ideal of the “total work of art”, which sought to express itself first in films and subsequently in video games, a medium whose every element can emit a sound or play a part in an orchestra, as in the case of the flora and fauna of the islands explored in Proteus (Ed Key, David Kanaga, Twisted Tree, 2013).

FINAL FANTASY X X-2 HD Remaster (Square Enix, 2016) image via Steam

In three-dimensional video games, the sounds take on three dimensions as well, signaling distances, directions and architectural features. Thanks to sounds, such as the blast of a weapon when it wakes a distant monster, unity is established among the worlds of one of the most influential of 3D video games: Doom (id Software, 1993). Indeed, without the interconnections supplied by sound, the gaming space would be nothing more than a series of juxtaposed rooms and hallways.

Precisely because video-game space can also be depicted through sound and music, there are digital games which rely on nothing but sound to denote places and events, making them not mere video games, but audio games which prove fully accessible even to blind or sight-impaired users.

Doom (id Software, 1993) image via Steam

As video-game historian Damiano Gerli notes, the first game specifically designed for the sight-impaired was an Italian work: Blindness (Dedalomedia, 1996). Blindness also has visual elements, in fact it makes use of photos of physical sites, as well as videos featuring live actors, including the lead character, played by Cesare Bocci, the same actor who has the role of Mimì Augello in the Italian TV series Inspector Montalbano. But at the same time, the different places are also brought to life by their distinctive sound and noises, while also being represented by a static image that can be entered using the mouse. Exploration of these settings is imitated by means of the cane of the lead character, a sight-impaired individual who comments on the elements provided for interaction.

Blindness (Dedalomedia, 1996), immagine via MobyGames

Looking at more recent audio games, the most noteworthy example is The Vale: Shadow of the Crown (Falling Squirrel, Creative Bytes Studios, 2021). In a make-believe medieval world, a blind princess, having fled to a remote province of her kingdom to escape an enemy attack, must return to her capital all on her own. The visuals are done from her point-of-view, on an almost completely black screen, with the fighting and defensive maneuvers carried out solely on the basis of the sound of enemy attacks and footsteps. Meanwhile, the cities and towns (three-dimensional spaces set in real-life scale) are navigated by relying on the sounds of the inhabitants and their activities, with various characters being identifiable by their distinctive accents and ways of talking. “Dialogues to me became more important because of the lack of visuals”, explains David Evans, the game’s director, in the course of a Zoom conversation. “How can you culturally define a diverse low-fantasy world?”

The Vale Shadow of the Crown (Falling Squirre, Creative Bytes Studios, 2021) image via Steam

In certain cases where video games are not fully navigable without the assistance of visual elements, users themselves have come up with more accessible versions. This occurred with one of the descendants of Doom, Quake (id Software, 1996), which, in 2003, was transformed into AudioQuake by Matthew Atkinson and Sabahattin ‘Sebby’ Gucukoglu, who used “earcons,” or “sound icons”, to provide each relevant object with a clearly identifiable position in space. In any event, and despite some residual uncertainty, today’s video-game industry is moving in the direction of options able to make every major game as accessible as possible, as in the case of the recent remake of The Last of Us Parte I (Sony Interactive Entertainment, 2022), which is now a television series too. The Last of Us Parte I comes with built-in screen readers for all its texts, plus audio descriptions of its filmed sequences, while the vibrations of the PlayStation 5 gamepad orient the players, who are also supplied with support tools for navigating spaces and identifying enemies and objects.

The Last of Us Parte I (Sony Interactive Entertainment, 2022) immagine via Epic Games Store

Taken as a whole, these experiences and experiments make clear the unmistakable interest of video games in forging their identities not only through visuals, but with audio as well, resulting in games that are able to fulfil the promise of interactive forms of audio theatre.