Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, DSL Studio

British visual artist Mark Leckey’s video work concludes the major exhibition dedicated to Elio Fiorucci, serving as the epiphany of a world that may no longer exist.

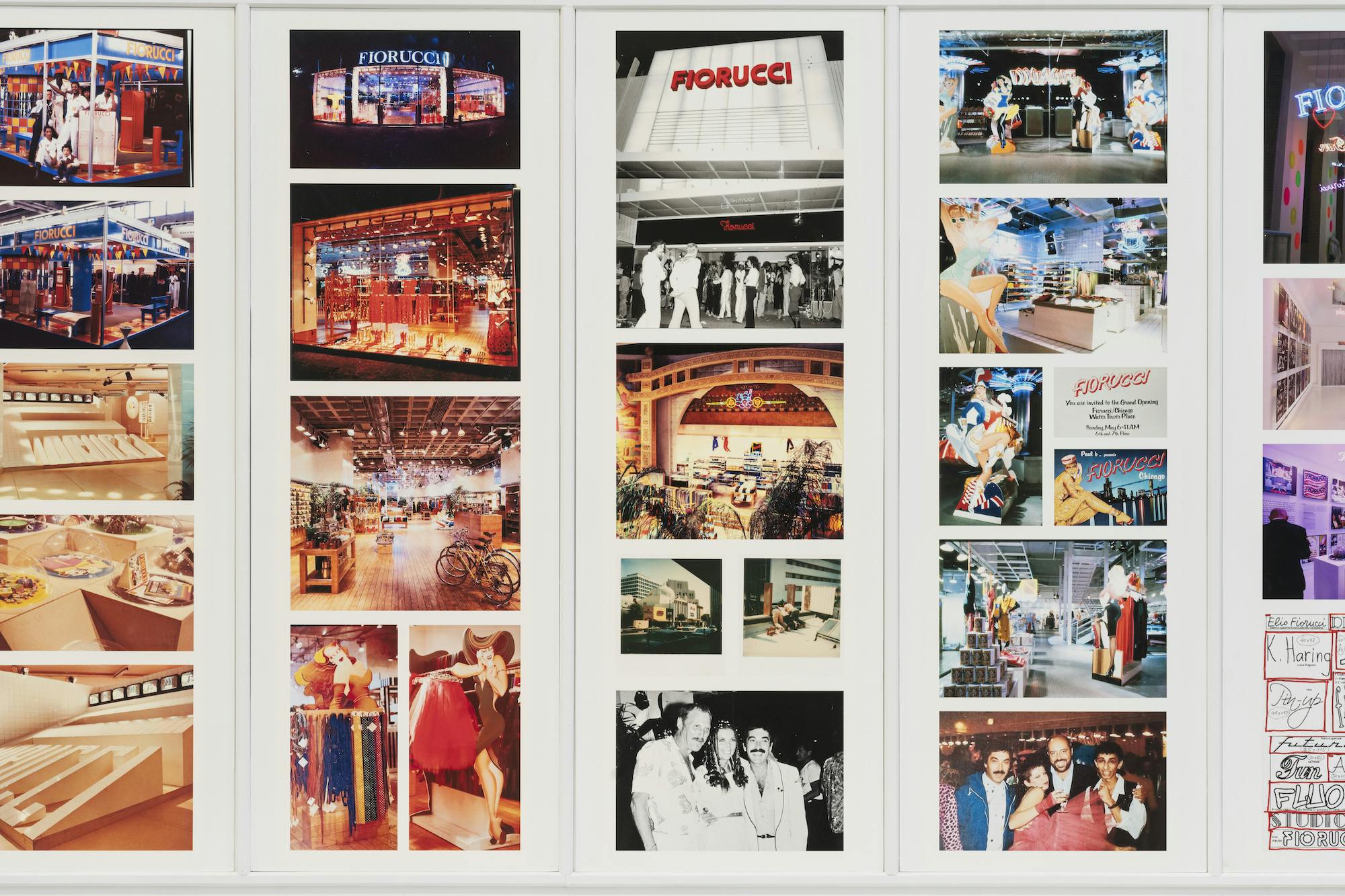

When visiting the retrospective exhibition dedicated to Elio Fiorucci curated by Judith Clark—an attempt not only to pay homage to his genius, but also to bring some order to the endless narrative developments underlying such a complex figure—one can imagine two possible lines of interpretation.

The most immediate is the diachronic approach, which invites the visitor to explore the character’s origins through Fabio Cherstich’s clever set-up. A stark elementary school room in 1940s Northern Italy—complete with a schoolchild’s desk and chair—visually introduces us to the dream, the imagination, and the pop explosion. A burst of neon fireworks appears in the distance through the window frame of that small room, already providing the visitor with a hint of what is to come: Fiorucci, the name, the brand, a story that even those less involved in the world of fashion and image have subliminally stored somewhere in their subconscious.

Installation view of Elio Fiorucci, photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, DSL Studio

Then there is another possibility: that of reversing the vision, such as by taking this telescope and looking through it in the opposite direction, trying to cheat the arrow of time and starting with the last work at the end of the journey. This is the video by British artist Mark Leckey, whose Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1999) produced one of the most powerful visual manifestos of British youth culture: a montage of sequences that mixes nostalgia and memory and was received early on as a kind of video treatise on sociology. Thus, starting from there and rethinking everything in between can be an interesting exercise in reflecting, from a different perspective, on what Fiorucci (the man and the brand) represented.

Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore sits at the heart of a broader reflection on the importance of subcultures, the evolution of fashion and music as social languages, and the very idea of collective experience. It represents not only a tribute to decades past, but also, and more importantly, a melancholy epilogue to a time when subcultures developed spontaneously and in opposition to the dominant culture, before the market swallowed up their authenticity.

In the work of Leckey—one of the most significant artists of his generation and winner of the Turner Prize in 2009—there is an ongoing exploration of the relationship between popular culture, technology, and collective identity. Born in 1964, he grew up in a Britain shaped by Margaret Thatcher and her neoliberal reforms, a context that fueled the rise of youth subcultures such as punk, rave, acid house, and northern soul.

Mark Leckey, 2024, photo by Alessandro Raimondo

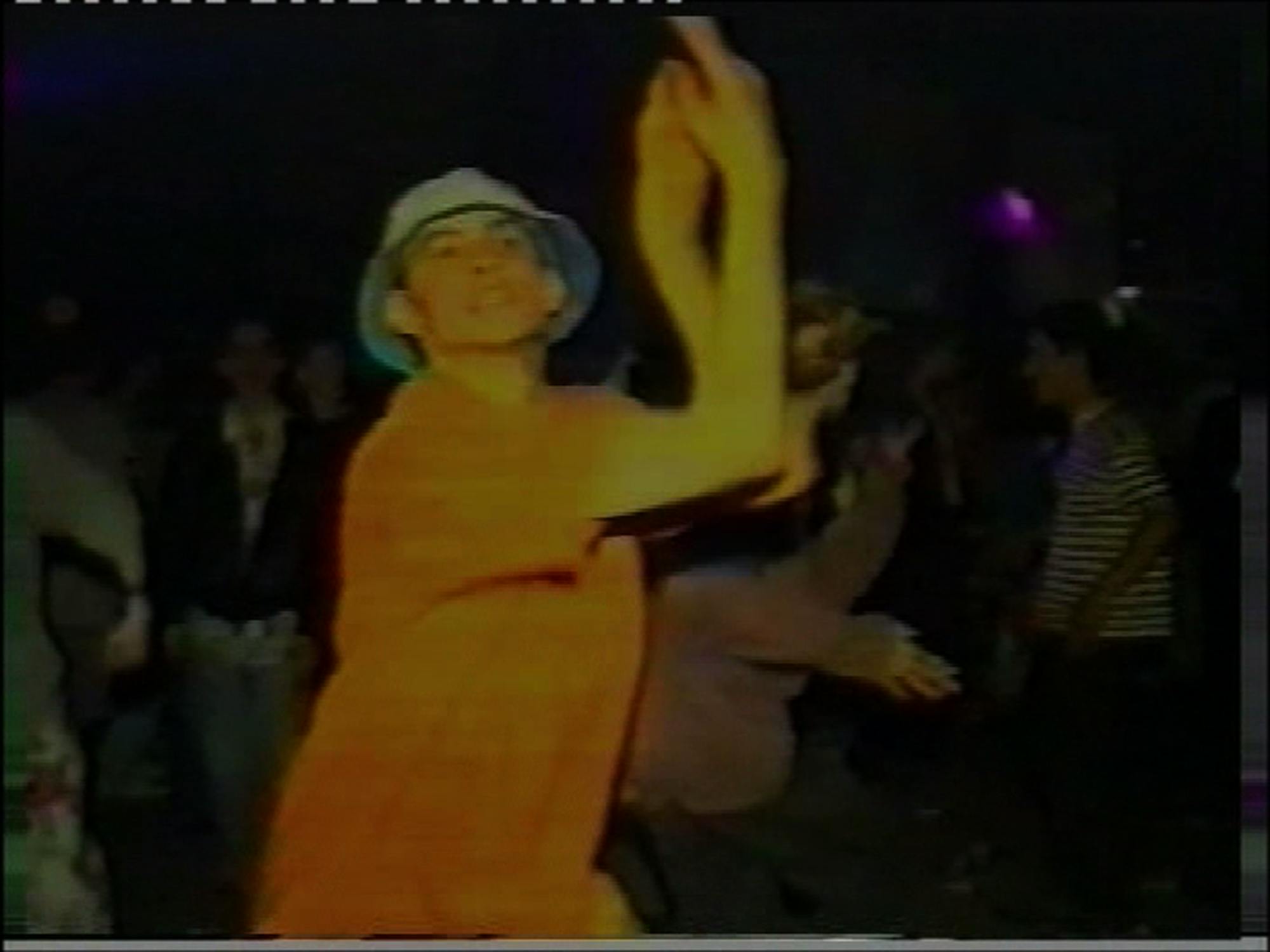

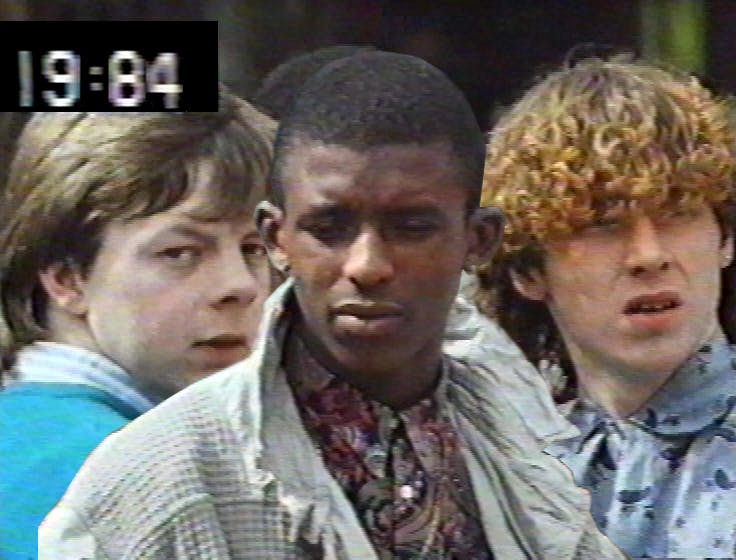

In Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, which, not surprisingly, was presented at the end of the last millennium in a group show at the ICA in London, the artist encapsulated thirty years of cultural evolution, from the disco clubs of the 1970s to the hardcore raves of the 1990s, using archival footage manipulated through experimental editing. Gaining cult status, the work is not only a documentary on youth culture, but a poetic and philosophical meditation on time, memory, and the meaning of collective experiences.

His style, situated somewhere between documentary filmmaking and music video editing, successfully captures the urgency and thrill of youth lived on the fringes of the mainstream. A procession of dancing figures reveals the club’s diverse inhabitants, the tribe of style, and the rituals of the night. Slow-motion footage of young people engaged in culturally coded dances alternates with images of uniformed police officers, while the brands embraced by this nocturnal tribe—most notably Fiorucci—are prominently displayed.

The question of speed and time seems central to the relationship between pop and art. Sex Pistols historian and biographer Jon Savage points out this distinction in “Speed”, the final section of Time Travel, a collection of essays written between 1977 and 1996. Savage identifies speed as a pivotal element in the evolution of pop, both as an iconography and as a lived musical experience—the flow of energy from Elvis to Pere Ubu’s Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo. In the introduction to Time Travel, he writes: “Speed is vital because it is one of the few areas where teens are more powerful than adults, and time has been frequently used to express a rebellious attitude. You need think only of Sly Stone exquisitely cocking a snook at the world in the lyrics of In Time.”

Installation view of Elio Fiorucci, photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, DSL Studio

The Fiorucci brand, referenced in the title, became a symbol of an era when fashion served as a creative and subversive form of expression. With its colorful, pop-inspired style, it captured the imagination of a generation eager to stand out through clothing that told a story. This link between fashion and identity is central to Leckey’s work. In the video, the progression of styles—from the bell-bottoms of northern soul to the casual outfits of 1990s clubbers—chronicles the evolution of social dynamics and the quest for belonging. Every young generation has sought not only an aesthetic expression in fashion, but a language capable of conveying tribal affiliations and rebellious ideals.

Leckey has appropriated various pieces of found footage to construct a sensory experience that evokes collective memory. However, the images are often slowed down, distorted, or repeated in a loop, creating a feeling of temporal suspension that reflects the fragmentary nature of memory. This is also apparent in the work’s sound dimension, composed of fragmented songs and ambient noises that heighten the sense of ambiguity—at once firmly rooted in a specific timeline yet timeless. It invites the viewer on a psychedelic journey through British cultural history.

Installation view of Elio Fiorucci, photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, DSL Studio

While his technique can be safely inscribed in the groove of the literary cut-up invented by U.S. writer William S. Burroughs—an intentional fragmentation that destabilizes the meaning of images and opens up new interpretive spaces—Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore seems to continue in the vein of other equally important experimental films, such as Rock My Religion (1984) by artist Dan Graham—whose works were recently exhibited at the Triennale—highlighting the affinities between artists who have used archival materials to explore the power of music and popular culture. While Graham focuses on the parallels between religious fervor and the energy of rock concerts, Leckey explores dance as both a means of transcendence and transformation, as well as a portrait of a crowd of bodies that would soon change forever.

Leckey does not follow a linear narrative. Instead, he moves between different times, blending dance scenes with moments of social interaction. The unifying element is dance, presented not only as a playful activity but as a collective ritual capable of transcending social and cultural barriers. Dance becomes the symbol of the ephemeral, an act that exists only in the present moment but leaves deep traces in emotional memory. The images of the dancers, caught in states of ecstasy and abandonment, evoke a secular spirituality, a sense of community that seems to defy the rules of the outside world. Nostalgia pervades the entire work, but it is not a simple or reassuring nostalgia. Leckey explores a complex feeling that combines melancholy and social criticism. In this context, nostalgia is not only a regret for a lost past, but also a lens through which to analyze the present. Indeed, it is the same sentiment that also permeates the entire exhibition dedicated to Elio Fiorucci, where that great chapter of Italian style, art, fashion, pop culture and entrepreneurship seems suspended in a time that we know was there and left its mark, but that it is difficult to find again in the present, either for those who were there, or also those who were not there and experienced it virtually.

What have we gained and what have we lost in the transition to a globalized and digitized world?

In this work and in Leckey’s other works, the artist seems to ask: what have we gained and what have we lost in the transition to a globalized and digitized world? In an age when subcultures form and dissolve as quickly as a social media post, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore also represents a warning, an intriguing monument to the impermanent.

This condition was described more than a decade later by British music critic Simon Reynolds in Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past (2011). The concept of “retromania” highlights the contemporary obsession with the past, where references are no longer simply quotations, but become real pillars on which the present is built. Memory merges with a constant sense of déjà vu—of things already seen, already heard, already worn—amplified by the ubiquitous presence of artificial intelligence, which intensifies this recursive temporality.

The video captures not only the artist’s personal memory but also the collective memory of a generation.

Leckey embraces this retromania, but at the same time questions it, highlighting how nostalgia can turn into a sterile refuge if not accompanied by critical reflection. While celebrating the youth culture of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, his video suggests that the value of subcultures lies in their ability to imagine a different future, not just regret an idealized past. The subcultures represented in the video are spaces of resistance to homogenization, yet Leckey does not overlook the inherent contradictions within these movements. The commercialization of subcultures and their transformation into mainstream fashions is an implicit theme in the work, reflecting the tensions between authenticity and appropriation.

Leckey has described Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore as an attempt to exorcise nostalgia for his own youth. After returning to England following several years in America, the artist found himself reflecting on his cultural identity and the significance of the experiences that shaped his upbringing. The video, with its fragmented and dreamlike aesthetic, is the product of this reflection—a work that captures not only the artist’s personal memory but also the collective memory of a generation.

The inclusion of Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore as the epilogue to an exhibition dedicated to Elio Fiorucci adds another layer of meaning to the work. The exhibition, with its celebration of fashion as art and language, finds in Leckey’s video a moment of symbolic closure, an invitation to reflect on what remains of that era of experimentation and creative freedom. The large, multicolored curtain that concludes the exhibition, placed immediately after the video screening, becomes a symbol of transition—a passage from the past to the present. The video images, often obscured by visual and sound effects, suggest that the past is never fully accessible. What remains are fragments, impressions, and sensations. This representation of the past as something incomplete and elusive is central to Leckey’s work and is part of his audiovisual lexicon, in this and other works.

Loden, installation view, photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, DSL Studio

Looking back over the entire course of the Elio Fiorucci exhibition with this approach makes it possible to deconstruct the pop signs, the logos, and to go back to the principle of an individual need: that of the creative child who wanted to escape from that school desk, and who grew up to understand the collective needs of the younger generation to express themselves through the apparent lightness of its products. However, Fiorucci never mingled with them: he always kept a distant gaze on things, wearing the bourgeois loden coat (a key exhibit in the exhibition), because ultimately those disheveled scenes of British clubs and Studio 54 in New York never really pertained to him like the workshops of Milan and the serene landscapes of Alto Lario.