A tribute to one of the most important international conceptual artists, Dan Graham, whose research explored the boundaries between art and architecture. We trace his career through the rich bibliography of thinkers and critics who have reconstructed and commented on his work.

Triennale Milano’s The Passing Time City exhibition is dedicated to Dan Graham (Urbana, 1942 - New York, 2022), a pivotal figure for anyone interested in the evolution of twentieth-century conceptual art. Looking back over his career via an extensive bibliography of thinkers and critics who reconstruct Dan Graham’s oeuvre and discuss the contributions he made, this Triennale Milano exhibition pays tribute to a leading international conceptual artist whose work mapped out the intersection of art and architecture. The exhibition features two large installations in the institution’s outdoor areas, and archival documentation at Cuore. Working with the Estate of Dan Graham and the City of Milan’s Office for Art in Public Spaces, Maurizio Bortolotti’s curation enables visitors to engage with the environmental dimension of works that pushed the very boundaries of perception.

Graham’s name frequently appears in bibliographic materials, particularly the broad number of essays on visual arts related to him, or in lists of his works owned in the collections of the world’s foremost international institutions. His name also constantly crops up in literature on the performing arts, architecture, musicology, even spiritual and mystical research – a fact that, on its own, demonstrates the artist’s ability to make a significant impact in his explorations of different media, at all times radically striving to question their nature and seek to go beyond his comfort zone.

Drawing on his analytical skills, from the mid-1960s Graham generated a fundamental body of works and theoretical writings on the historical, social, and ideological functions of contemporary cultural systems. Graham covered the macro-themes of architecture, popular music, video, television and more in essays, performances, installations, videotapes, and environmental projects such as the ones in The Passing Time City.

Through perceptual and psychological exploration spanning the public and private spheres, as well as embracing both beholder and performer, in the early 1970s the artist embarked on creating installations and performances that actively involved the viewer. Graham broke down the phenomenology of seeing to reenvision space, time and audience engagement. Many of his earliest installations utilized closed-circuit video systems in designated performance spaces, altering viewers’ perception through delays and delayed projections to craft an aesthetic reminiscent of surveillance systems and the nature of reflective surfaces. By way of example, in Performance/Audience/Mirror (1975), the artist positioned himself in front of a mirror-clad wall and meticulously described his body movements in relation to the audience looking on. A video camera directly captured the continuous shifts between subjective and objective perspectives, to be mirrored alongside the artist and audience. This framing turned the image into a kind of “subject” itself, transforming Graham and the spectators into objects. Initially, the audience viewed itself as an “image” in the mirror, and yet in the videotape of the event, both audience and artist bec0me a subject to be viewed by a potential third viewer.

Alongside other early works, such pieces pushed the conceptual research envelope, probing the interplay of relations between body, space, and sexuality, the role of the media eye as a guardian of action- and time-related memory, and potential narrative manipulation of reality. Artists like Bruce Nauman, Vito Acconci, Gina Pane, and Michael Snow in cinema or Alvin Lucier in music had grasped the neutrality of the medium’s perspective, prefiguring issues and concerns that, in our day, may erroneously be deemed “resolved” in what neurosciences term the specious (or continuous) present.

See, for example, Graham’s 1974 Present continuous past(s), discussed in his essay Video-Architecture-Television (New York University Press, 1979): “The mirrors reflect present time. The video camera tapes what is immediately in front of it and the entire reflection on the opposite mirrored wall. The image seen by the camera (reflecting everything in the room) appears 8 seconds later in the video monitor (via a tape delay placed between the video recorder which is recording and a second video recorder which is playing the recording back). If a viewer’s body does not directly obscure the lens’ view of the facing mirror, the camera is taping the reflection of the room and the reflected image of the monitor (which shows the time recorded 8 seconds previously reflected from the mirror). A person viewing the monitor sees both the image of himself, 8 seconds ago, and what was reflected on the mirror from the monitor, 8 seconds ago of himself which is 16 seconds in the past (as the camera view of 8 seconds prior was playing back on the monitor 8 seconds ago and this was reflected on the mirror along with the then present reflection of the viewer). An infinite regress of time continuums within time continuums (always separated by 8 seconds intervals) within time continuums is created. The mirror at right-angles to the other mirror-wall and to the monitor wall gives a present-time view of the installation as if observed from an ‘objective’ vantage exterior to the viewer’s subjective experience and to the mechanism which produces the piece’s perceptual effect. It simply reflects (statically) present time.”

Graham’s insights closely align with how, often unconsciously, we today interact with space and with the altered or distorted timing of every video call and digital-mediated relational mode. Critic and curator Roselee Goldberg points out that Graham explored alienating effects theorized by Bertolt Brecht, linking the performer and audience not just through performances but through architectural space design, as in the pavilions showcased at the Triennale: Sagitarian Girl (2008) and London Rococo (2012), both of which cite architectural motifs not to evoke “other” experiences and narratives, but to foster an awareness of material. Shorn of their assumed functions (through paradoxical transparency, protecting, enclosing and displaying), the materials enable visitors to critically distance themselves from solutions that pervade and arrange public spaces. Maurizio Bortolotti suggests Graham “reimagined the pavilion typology starting from material that critiques the use of glass in corporate buildings, conveying an idea of surveillance in the urban landscape. Audience interaction with his pavilions ushered in a different form of engagement for art audiences. In Graham’s designs, the audience looks like more ordinary individuals navigating modern urban life, breaking down the very concept of an expert audience.”

Rather than adopting what might seem the most direct approach for a sculptor (a term that hardly fits him, in truth), Graham explored space extensively through a diverse range of media. In Dan Graham’s Kammerspiel (1988), one of the most profound essays any artist has ever written on a fellow artist’s work, Canadian photographer Jeff Wall’s pre-eminent mind cited “an unrealized and possibly unrealizable project” by Dan Graham, Alteration to a Suburban House (1978). Wall considers this a work in which conceptualism merges three of the century’s most significant architectural motifs (the glass skyscraper, the glass house, and the suburban home), generating a monumental expression of apocalypse and historical tragedy.

Like other commentators, Wall highlighted Graham’s use of photography as a tool for dissecting the serial nature of architecture and industry. Consider, for instance, his seminal work Homes for America (1965-1967/2010) which far from being merely an aesthetic catalog of urban and suburban landscapes is actually a very interesting analysis of sociological and urban planning.

Spanish architect and media archaeologist Beatriz Colomina wrote several essays on the impact of Graham’s work. In her essay collection (“October files,” vol. 11, edited by Alex Kitnick, The MIT Press, 2011), the discussion turns to the facade of suburban homes, specifically the significance of the picture window from a domestic space perspective: “The picture window becomes a key feature of the post-war American house, transforming structure into a display of domestic life. That is not to say that the house reveals its interior in the expected way. Indeed, no interior is actually on show. The large window presents not a private space but a public portrayal of conventional domesticity, in Graham’s terms an embodiment of ‘socially accepted normality.’ The picture window acts like a storefront, advertising the middle-class American dream, or as a billboard that fails to attract the gaze of passersby for long: passersby do not closely inspect the scene, they take a quick glance and then move on, as if not wanting to know too much, ensuring they notice nothing unusual beyond that furtive glance... It’s not about passersby being polite. Rather, it’s about their identity being put at jeopardy. In the suburbs, the passerby is the one who is truly exposed, vulnerable to myriad unseen eyes behind each window, shutter or curtain. Curious, relentless eyes. No restrictions here. Every pedestrian under suspicion. An intruder.”

Like few others, Graham’s photography, video, and deconstructive architecture tirelessly sifts through these spatial and social interstices to deconstruct the dogmas of modernism and the rhetorical forms of presenting materials and documents within art spaces. Above all, Graham heralded a dialectic between the perception of oneself and other bodies, rendering viewers aware of everything a simple reflection can reveal about an individual in the broader relationship with the social spaces they inhabit.

Credits

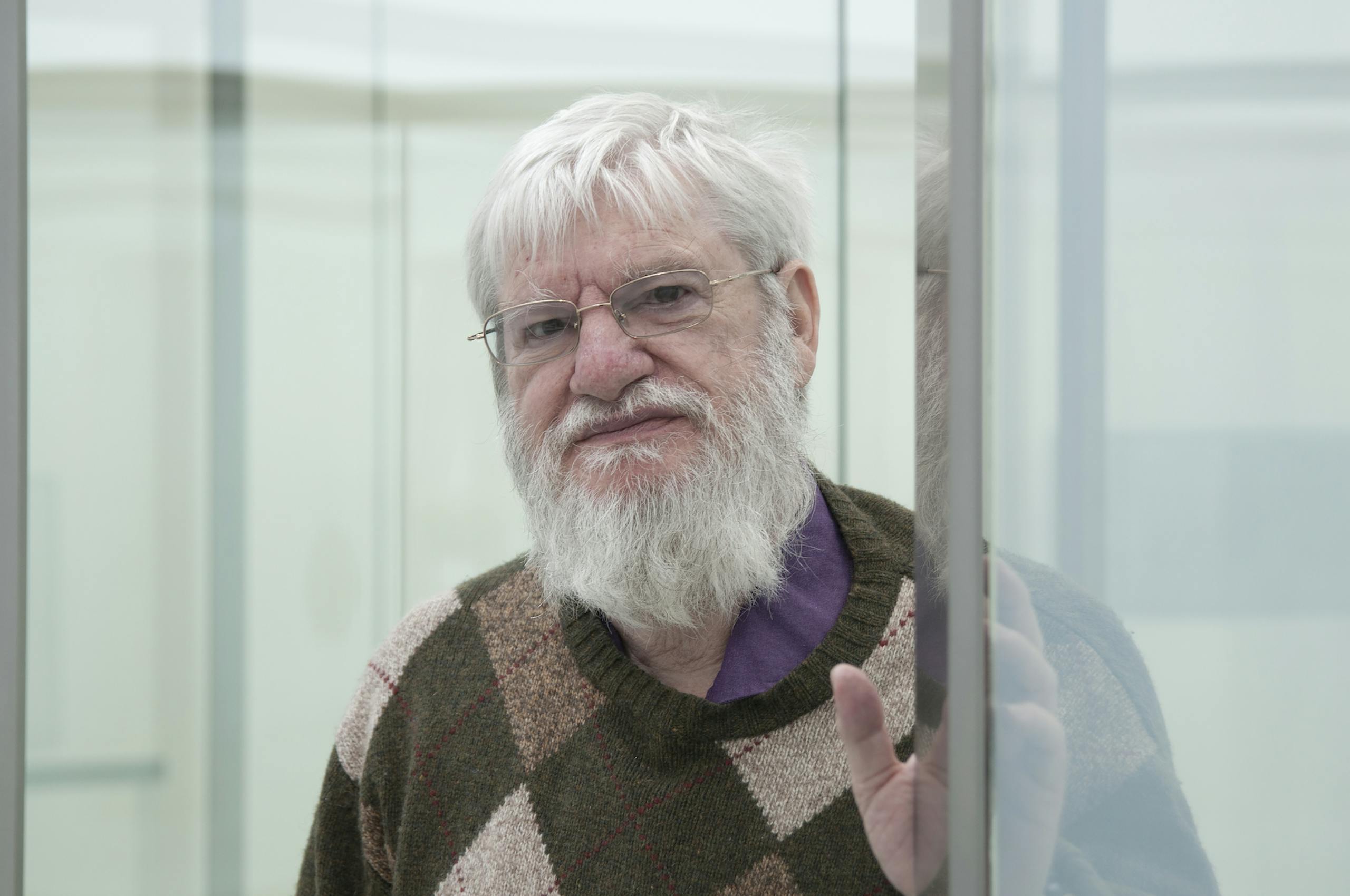

All photographs are installation views of the exhibition at Triennale The Passing Time City (through May 12, 2024), curated by Maurizio Bortolotti and in collaboration with Estate of Dan Graham and the City of Milan's Office of Art in Public Spaces.

All photographs: Gianluca Di Ioia

Related events