Antibiotic, SETI Interstellar Library

Jonathon Keats tells about The Library of the Great Silence in Fontecchio, Abruzzo

In the Italian village of Fontecchio, deep in the region of Abruzzo, stands a deconsecrated church built on the ruins of a temple once dedicated to Jupiter. During an artist residency last summer, I spent long hours sweeping the brick floors of the abandoned Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria, clearing away years of debris.

The church captured my imagination as an unintentional monument to societal transition, where a thousand-year succession of cultures and belief systems had been accidentally preserved in the architecture, now exposed all at once by the ravages of time. If I were asked by visitors from another planet to recommend places that reveal facets of human nature, I might guide them to this site.

In fact, that’s the reason why I spent part of my summer in a cloud of ecclesiastic dust. For a brief period in August, the abandoned Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria became the first setting for an omni-locational facility where beings everywhere will be able to study the characteristics that sustain or annihilate civilizations, from Earth to the outer reaches of Andromeda.

The Library of the Great Silence in Fontecchio

I call this facility the Library of the Great Silence, and I was inspired to build it by the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Enrico Fermi. Back in 1950, Fermi was discussing extraterrestrial intelligence over lunch with several fellow scientists. Responding to the claim that intelligent life must be commonplace throughout the universe, Fermi famously asked, “Where is everybody?”

With this conundrum, known as the Fermi Paradox, he called attention to the fact that a universe teeming with intelligence would likely be obvious to us. To explain the absence of extraterrestrial contact, commonly referred to as the Great Silence, scientists have hypothesized a Great Filter: Life must pass one or more crucial technological thresholds in order to colonize interstellar space. Some unknown aspects of societal advancement appear to be self-defeating for the majority of advanced civilizations.

The Great Filter has gained plausibility with the rise of existential threats ranging from the Cold War to anthropogenic climate change and mass-extinction. This range of threats suggests that some civilizations may have successfully averted certain perils that could lie in the future for others. Each has the potential to learn from this collective history, given a commons for sharing experiences of potentially existential significance.

Working in collaboration with the SETI Institute, I conceived the Library of the Great Silence as a common space to explore conditions for survival and flourishing. After prototyping a branch in Fontecchio, I’m now searching the world for other sites with a storied past that can be redirected toward consideration of the future. Each of these branches will be created in partnership with local communities. One is now underway in Hungary. Another will soon be launched in Australia. The headquarters, currently in early planning, will be situated at the Allen Telescope Array in Northern California, where the SETI Institute is conducting the most comprehensive search for extraterrestrial intelligence ever attempted by humankind.

At the most fundamental level, the Library of the Great Silence is a repository of transitions, such as the religious transformation from Paganism to Christianity preserved in the Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria. These transitions need not be changes for the worse. What is important is that they have a lasting impact. Those who use the library are challenged to figure out the implications and consequences, in order to inform future decisions.

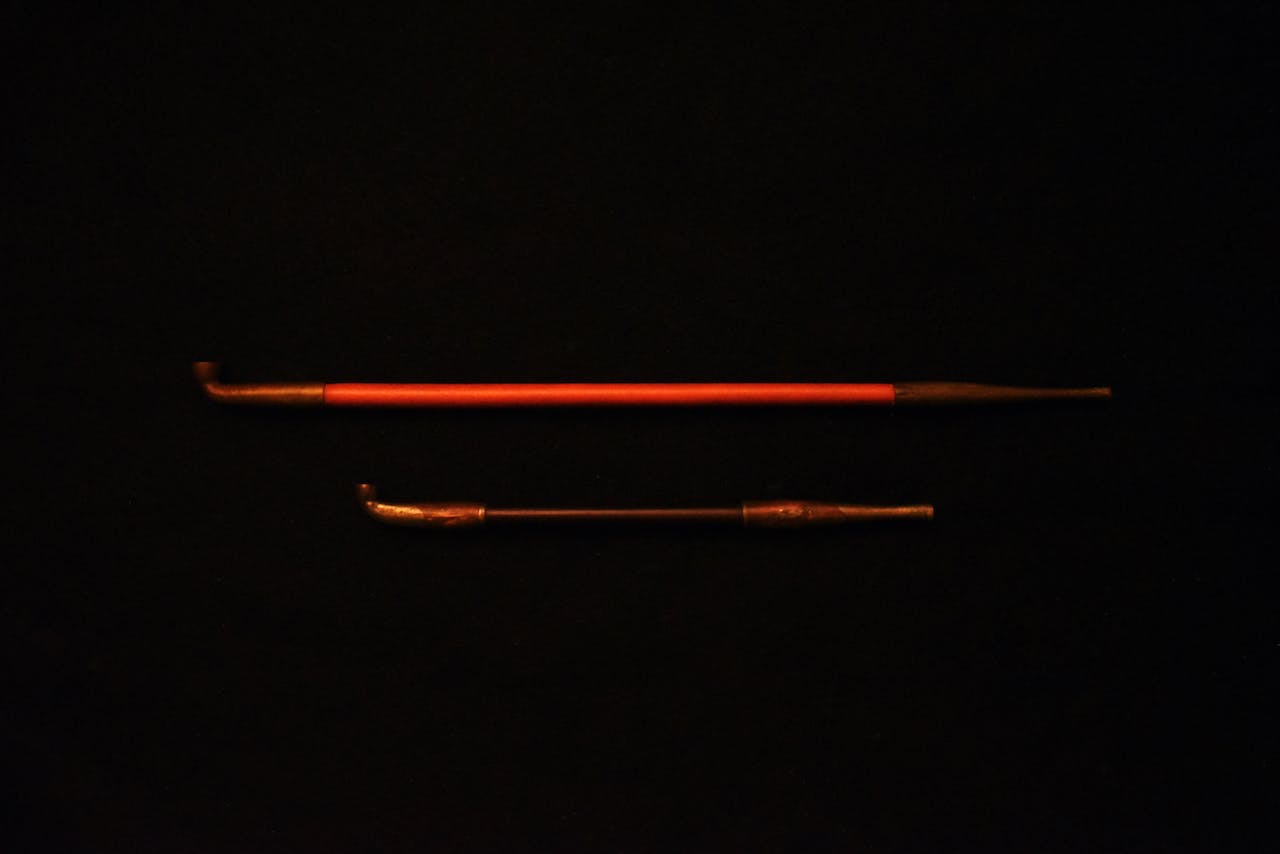

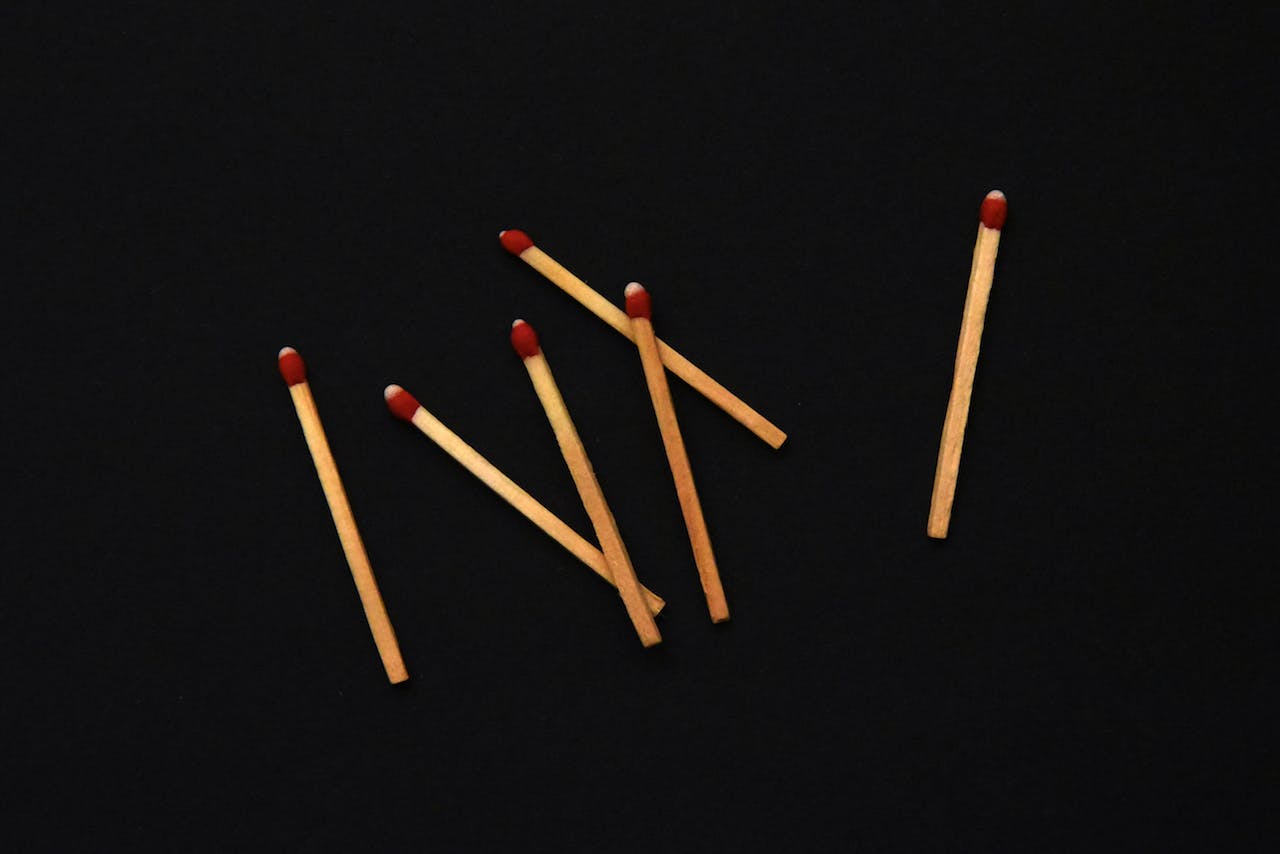

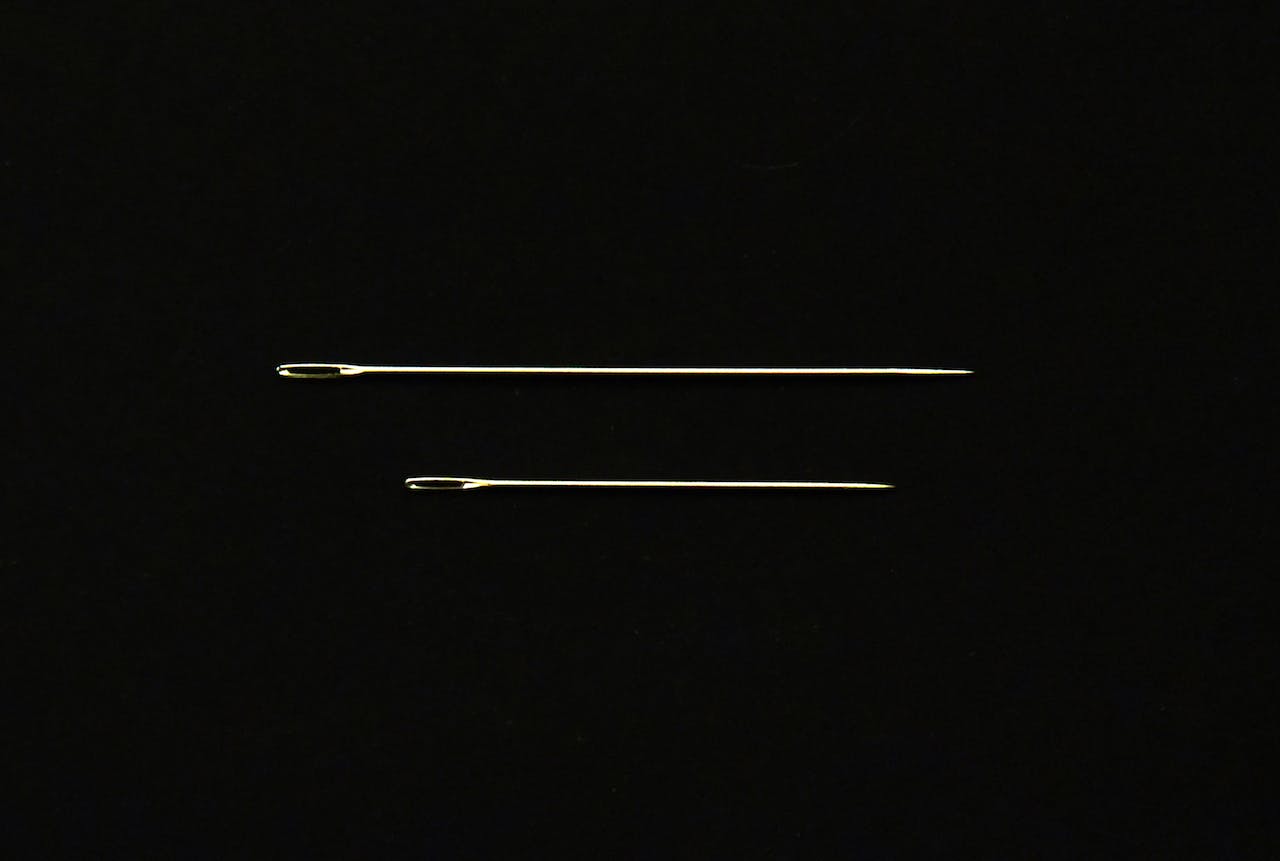

Because my intention is that the library be universal and equally accessible to all, the collection doesn’t focus on written materials or images that depend on symbolic representation. Instead, the library is an archive of objects. These artifacts range from prehistoric handaxes with which early hominids first altered their environment, to blocks of concrete with which we build modern cities. Other items include money, alcohol, and the birth control pill. I have sourced some exotic materials, such as samples of trinitite, the mineral created by the first atomic bomb explosion. But most of the objects are so commonplace that their significance might be overlooked if not for the context. For example, the branch in Fontecchio accessioned playing cards and canned fish. Our world has been radically changed by gambling and food preservation.

I do not claim to be an authority on transformations. When it comes to existential questions, everybody has a vital perspective. I believe that the best way to build a library is to work communally, through an open process of nomination. In Abruzzo, this resulted in inclusion of detritus from the devastating L’Aquila earthquake of 2009. Nomination is a form of communication, surfacing concerns such as worries about rebuilding in geological conditions that have repeatedly decimated cities and villages. Is reconstruction an act of hope or hubris? Does the underlying impulse help us to overcome adversity or exacerbate calamity?

The library is designed for rigorous examination of problems without obvious solutions. Following the process of nomination, materials are available for collective research into existentially threatening phenomena such as complexity and overreach. Language is not required. Simple devices are provided to physically express relationships between objects. For instance, a lever can convey the political leverage afforded by money.

SETI ATA photos of Jonathon Keats © Vincenzo Mancuso

The physical principles of leverage are the same everywhere, from Earth to Andromeda. Devices such as a lever allow beings from everywhere to interact, facilitating intergalactic dialogue about existential filtration events – if we aren’t alone, and provided that beings from elsewhere ever come to Earth bearing their own artifacts.

Even if we never receive extraterrestrial visitors, a material archive of transformations will have global value that may be sufficient to extend the lifespan of human civilization. Manipulating existentially significant objects without the use of words – and without the underlying assumptions of language or limitations on who participates in the conversation – may facilitate comprehension of human behaviors that has previously eluded us, or even directly encourage beneficial practices such as cooperation. And the collective effort of nominating and compiling materials for the Library of the Great Silence may inspire awareness of our precarious situation, inspiring greater responsibility.