Meredith Monk live with Katie Geissinger and Allison Sniffin

Meredith Monk

February 18 2023, 6.30pm

SOLD OUT

Cellular Songs, 2018, BAM Harvey Theater, Brooklyn, NY, foto Stephanie Berger

In the 1970s, Franco Quadri, a Milanese critic and curator of the new theatrical avant-garde, surveyed those performance experiences that he saw as radically re-imagining the contemporary scene, poised between the United States and Europe. “Inventions of a different theater,” which forgot the sometimes betrayed tradition of texts and words, instead exploring other occasionally fragile and impermanent possibilities of language and bodies. Quadri placed Meredith Monk, one of the most exceptional figures in international performance art, as the only female within this creative mosaic.

Having graduated from Sarah Lawrence College in 1964, as a child Meredith Monk had attended Dalcroze eurhythmics sessions, a technique that combines music with movement. She moved to New York after graduating, where she started performing, primarily in galleries and churches, including Judson Church, although she was not a member of the congregation. As the third element after voice and movement, theater completed her profile like one of the three corners “in a triangle,” as she herself stated.

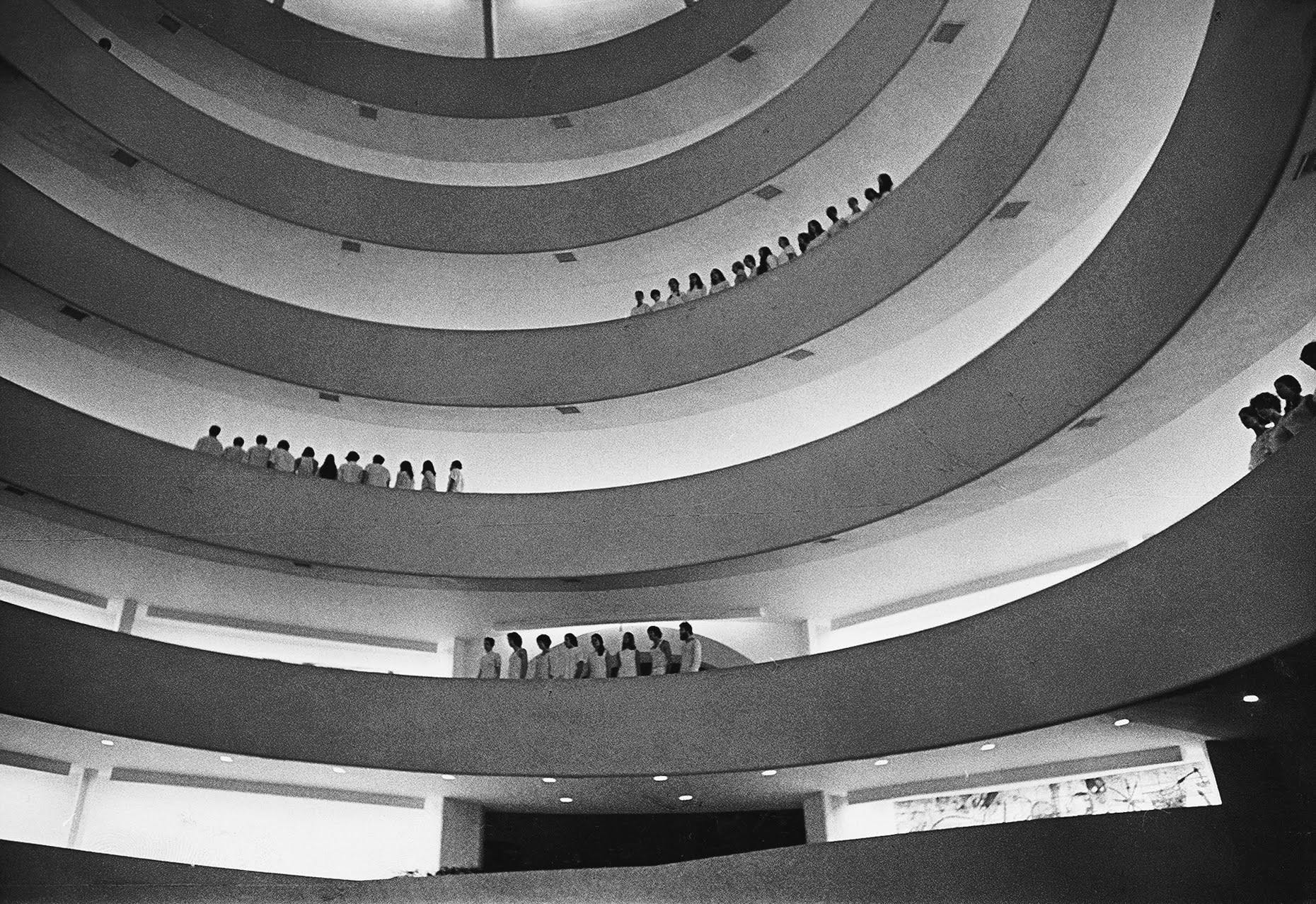

Juice: a theatre cantata in three installments, 1969, Guggenheim Museum, foto V. Sladon

In approaching the stage the first few times, her choreographic mindset directed her own exploration of the space: immediately intolerant of the constraints imposed by the theatrical black box, Monk began to explore new environments and architectures, new temporalities, both within reality and along more imaginative lines. After an initial experimental phase, Monk founded The House collective in 1968, devoting herself to very intense performance production work, which was often site-specific and moved outside the traditional spaces devoted to performance arts. In 1978, marking the culmination of a long decade of experimentation with voice and sound, she founded the Meredith Monk & Vocal Ensemble: a mobile device, traversed by diverse voices and musicians, that activates and regenerates an extraordinary repertoire of music and performance spanning more than sixty years in different formats. The ensemble will perform in concert on February 18, 2023, at the FOG festival as part of the Triennale.

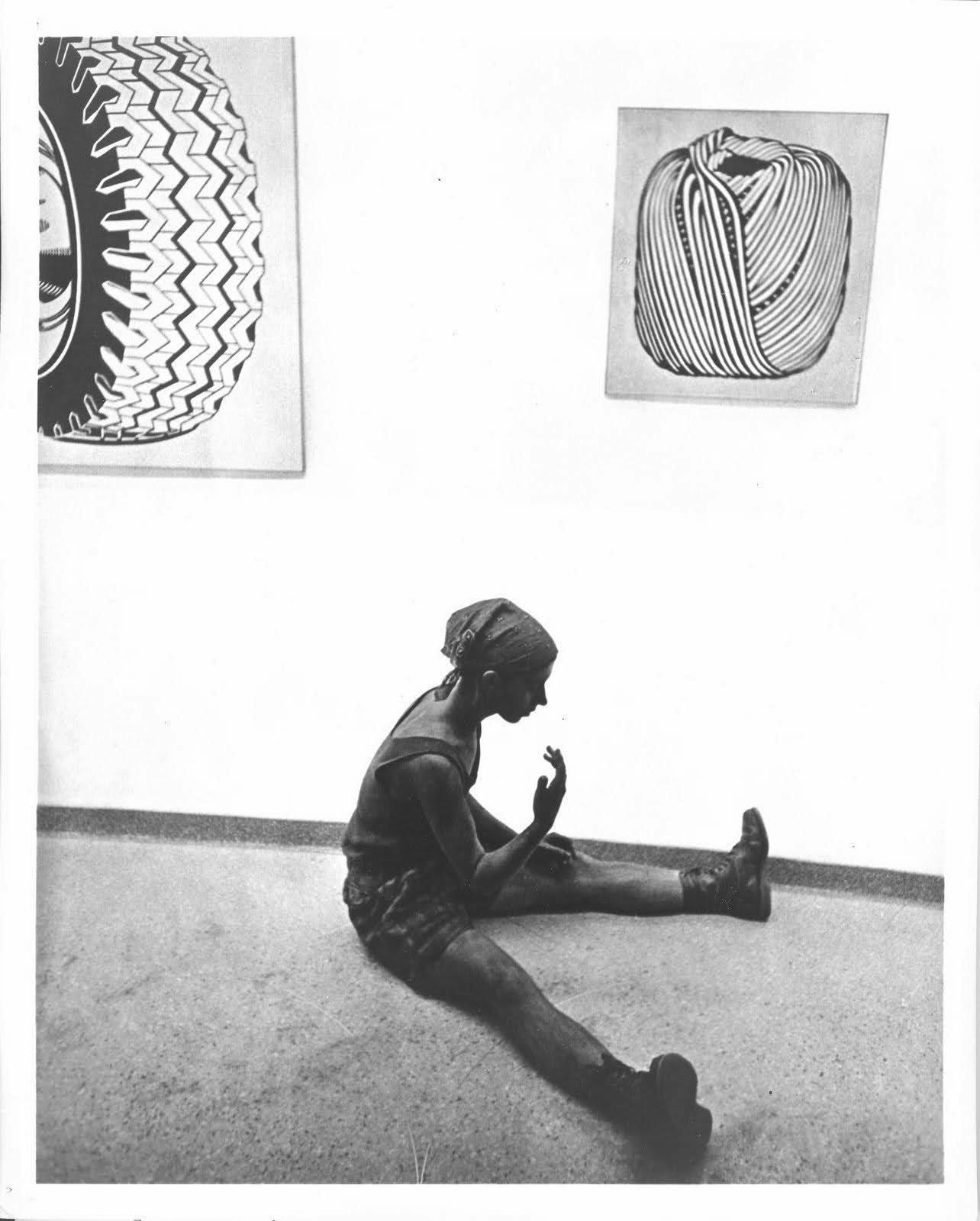

Education of the Girlchild, 1973, Venice, Italy, photo Lorenzo Capellini

Going back to Quadri’s recognition, one cannot fail to mention the distinction, suggested by the artist herself, between the two coalescing groups within her work, one concerning landscapes and the other portraits. In the text by Robb Baker, translated by Quadri into Italian with the title Cronaca in molti paesaggi (e qualche ritratto) and originally published in 1976 in Dancemagazine, we read how Meredith Monk described her longest performances as landscapes and compared them to a style of flat painting, with no raised surfaces; while her shorter pieces she called portraits. In actual fact, almost all her works are a combination of both and contain both the panoramic dimension and the portrait aspect. While the idea of the landscape is related, not only on a visual level but also in terms of sound and perception, to that of the symphony and the poem, the idea of the portrait follows the sonata and poetry.

Monk’s “landscape” works are the result of research conducted primarily in the 1970s, which is why they drew Quadri’s attention. One of the best examples in this category is Vessel (1971), a work that the artist describes as epic even in its subheading. Vessel is conceived in two phases. The first begins in Monk’s loft – where some nearly motionless characters appear from the dark, including Meredith/Saint Joan playing an organ – before moving to a bus (carrying viewers), and ends at the Performing Garage, the historic home of Richard Schechner’s Performance Group. The second takes place outdoors in a parking lot, where a battle erupts between armies, noises, and songs, leaving Monk/Saint Joan alone and intent on sacrifice. Like the other landscape and symphonic works, Vessel is broken down into several events and is staged in different places. The landscape moves out of the physical space of the theater and linear and historical time, combines the complex tales of the tapestry and the hints of the sketch, features the crowds and the solo, the solemnity of song and the vulnerability of the whisper, inhabits natural and fantastic dimensions, and flows with evident speed and hidden pauses.

Songs of Ascension, 2008, Walker Arts Center, Minneapolis, MN Meredith Monk, foto Cameron Wittig, courtesy Walker Art Center

The “portrait” works, on the other hand, have a more traditional format and venue, with the experimentation shifting from the geographies of the settings to the choreographics of the voice and of movement. In Songs of Ascension (2008) – which Monk discusses in conversations with Bonnie Marranca – her research travels from the monumentality of exteriors into the minimal atmospheres of the body, heart rhythms, and vascular flows, to the vision of DNA as a continuous spiral, a possible form of sound wave. DNA can feature theatrical singing, gestures create music, sounds sculpt perceptions: cantatas that support prayers ascend and carry upwards, but is there a possibility of song not having to grow and rise and instead go down, even underground?

Juice, 1969, Guggenheim Museum, NY, foto V. Sladon

In conclusion, Monk’s work as a whole reduces every distance, dismisses the hierarchies of value that subject visions of the impossible, the intimate, the dreamlike, and the fantastic to the supposedly greater laws of the visible, of logic, and of reality. She pursues a horizontal form of theatricality, in which bodies, objects, costumes, spaces, and lights do not serve and “function” for a purpose, but work together and participate in the scene with a presence that is sometimes even just affective. And The House, which is the chosen place of affection, of intimate and private life, multiplies and also becomes a space of public and collective artistic creation. An alchemist’s laboratory populated by events, memories, dreams, ghosts, collective childhoods, oracles, and near futures. Ultimately, Monk sees theater as a form of magic.