Photo by Unsplash

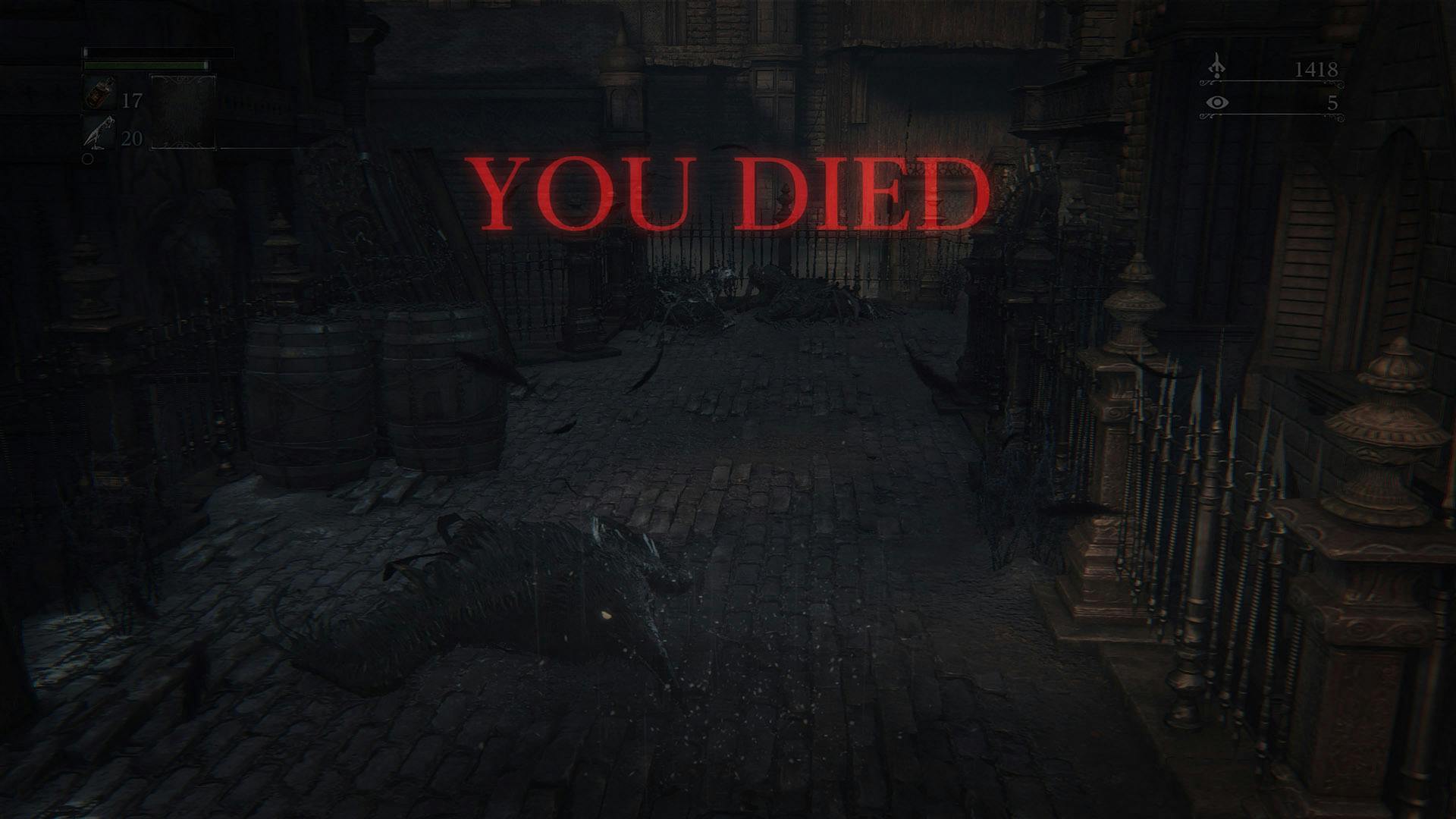

In 2013, Danish scholar Jesper Juul inaugurated MIT Press’s Playful Thinking series with an essay titled The Art of Failure, in which he used this expression to define the medium of video games. What Juul noted is that our experience of most mainstream video games is primarily one of failure: most of our games end with the character falling off a cliff, being shot down in a gunfight or exploding in a car, only to resurrect and die again and again. Such failures are not an end in themselves: according to Juul, they are unpleasant and we would rather avoid them, but they are nonetheless necessary to achieve the final victory, the moment when we finally manage to complete the level or mission. Gaming and video games are safe and socially accepted spaces where we can experiment, fail and learn from failure in ways that would not be possible in everyday life, but according to Juul the pleasure of video game failure lies in the promise of overcoming it.

Bloodborne (FromSoftware, Sony Computer Entertainment, 2015)

In essays later revised and collected in Video Games Have Always Been Queer (NYU Press, 2019), Bo Ruberg drew on Juul’s insights and combined them with those of Jack Halberstam (The Queer Art of Failure, Duke University Press, 2011). In a society which equates success with adherence to specific rules and specific life stages, failure is queer. “Queer” is used here not only in terms of sexual orientation and gender identity, but more broadly as anything that escapes the “straight and narrow” of a cisheteronormative and capitalist culture that only accepts what is productive and reproductive. Something is queer when it deviates and errs, and in doing so – says Halberstram – suggests alternative ways of living. If video games are the art of failure, and failure is queer, then video games, as Ruberg writes, “can be seen as fundamentally queer”. In short, there is pleasure – queer pleasure – in video game failure, in finally having the opportunity to freely experience what we have always been told we cannot, and in the possibility of rejecting even the rules of the game itself in order to deal with it in ways that are deemed wrong.

If video games are the art of failure, and failure is queer, then video games can be seen as fundamentally queer

There is a whole genre of games, known as silly games, that revolve around the pleasure of failure. As C. Thi Nguyen argues in Games: Agency As Art (Oxford University Press, 2020), these games, which include the popular Twister, are meant to be played with the goal of winning, but are remembered for the spectacular failures in which they end, made all the more memorable by the effort players put into them.

BloodbornePSX (LWMedia, 2022)

Dark Souls Remastered (QLOC, FromSoftware, Bandai Namco Entertainment, 2018)

Failure also plays an important role in contemporary video production. Videos of “epic fails” (failures so catastrophic that they can be considered “epic”) are among the most popular types of content on video-sharing platforms such as YouTube and TikTok. Along with classic candid camera footage and certain moments from reality TV and talent shows, they are part of what Sarah Booker and Brad Waite have called “humilitainment”. The pleasure of watching a video of someone who, having run out of hairspray, decides to replace it with a very powerful spray glue (as in the case of Tessica Brown, known as “Gorilla Glue Girl”) could be seen as an example of schadenfreude, the joy of witnessing others’ misfortune. But following the argument we made about video games, the popularity of these videos might instead be linked to the possibility they give us of experiencing failure, even in its queer dimension, albeit in a delegated form.

Elden Ring (FromSoftware, Bandai Namco Entertainment, 2022)

The concept of “interpassivity” was first proposed by Robert Pfaller in 1996 (his essays on the subject are collected in Interpassivity, Edinburgh University Press, 2017). It was later also developed by Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek. We are used to the idea that we can delegate certain tasks, but what we often delegate is actually feeling something, enjoying something – and sometimes we delegate pleasure. A classic example is provided by Jacques Lacan in his Parisian seminars (The Ethics of Psychoanalysis 1959-1960, Routledge, 2008): in Greek tragedy, the chorus is tasked with experiencing suffering and fear instead of the spectators. Žižek (The Sublime Object of Ideology, Verso Books, 1989) shows how the phenomenon also exists in contemporary entertainment: the fake laughter of sitcoms laughs instead of us. The sitcom does it all by itself; it even replaces us in our enjoyment. It is interpassive in the sense that our passive (unproductive) consumption has been delegated, in this case to the very object we are consuming, as opposed to what happens with interactive art, which delegates part of the active and productive process to us. And this delegated passive enjoyment is itself a specific pleasure, no less so than that associated with interactivity. Likewise, the pleasure of passive enjoyment is in no way inferior to that of active enjoyment. Besides, even in these usual hierarchies we might notice a certain patriarchal and cisheteronormative bias. From this perspective, epic fail videos could be seen as an interpassive mode of enjoying the pleasure of failure.

DarkSouls 3 (FromSoftware, Bandai Namco Entertainment, 2016)

Dark Souls Prepare to Die Edition (FromSoftware, Namco Bandai Games, 2012)

Video games, with their endless sequences of failures, provide a wealth of content for such videos, which are posted directly by the people responsible for the failures and then organized and shared as edited compilations. Those who upload their gameplays in these formats and as Let’s Play videos (recorded gameplays distributed in an episodic format, usually with commentary), but also those who play games on live-streaming platforms such as Twitch, do not simply allow us (not) to play through their gaming. Those who create such works also become the chorus of a video game tragicomedy that enacts failure and through which we secretly enjoy failure.