Voci dal Mondo Reale

Alexis Paul – Alessandro Sciarroni – Folk choirs

November 11 2022, 8.00pm

SOLD OUT

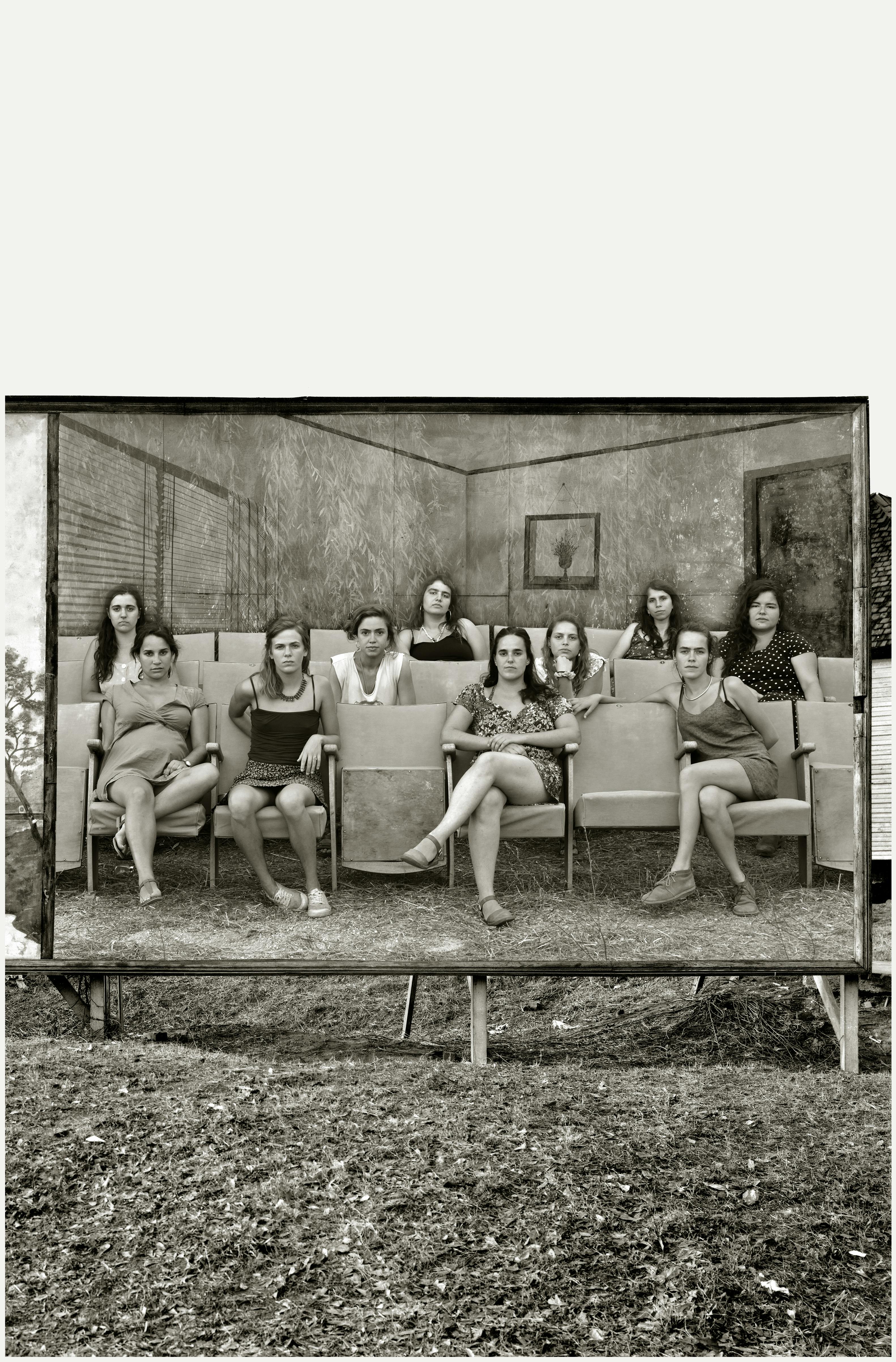

Alexis Paul and Alessandro Sciarroni, ph. Lisa Surault, Andrea Macchia

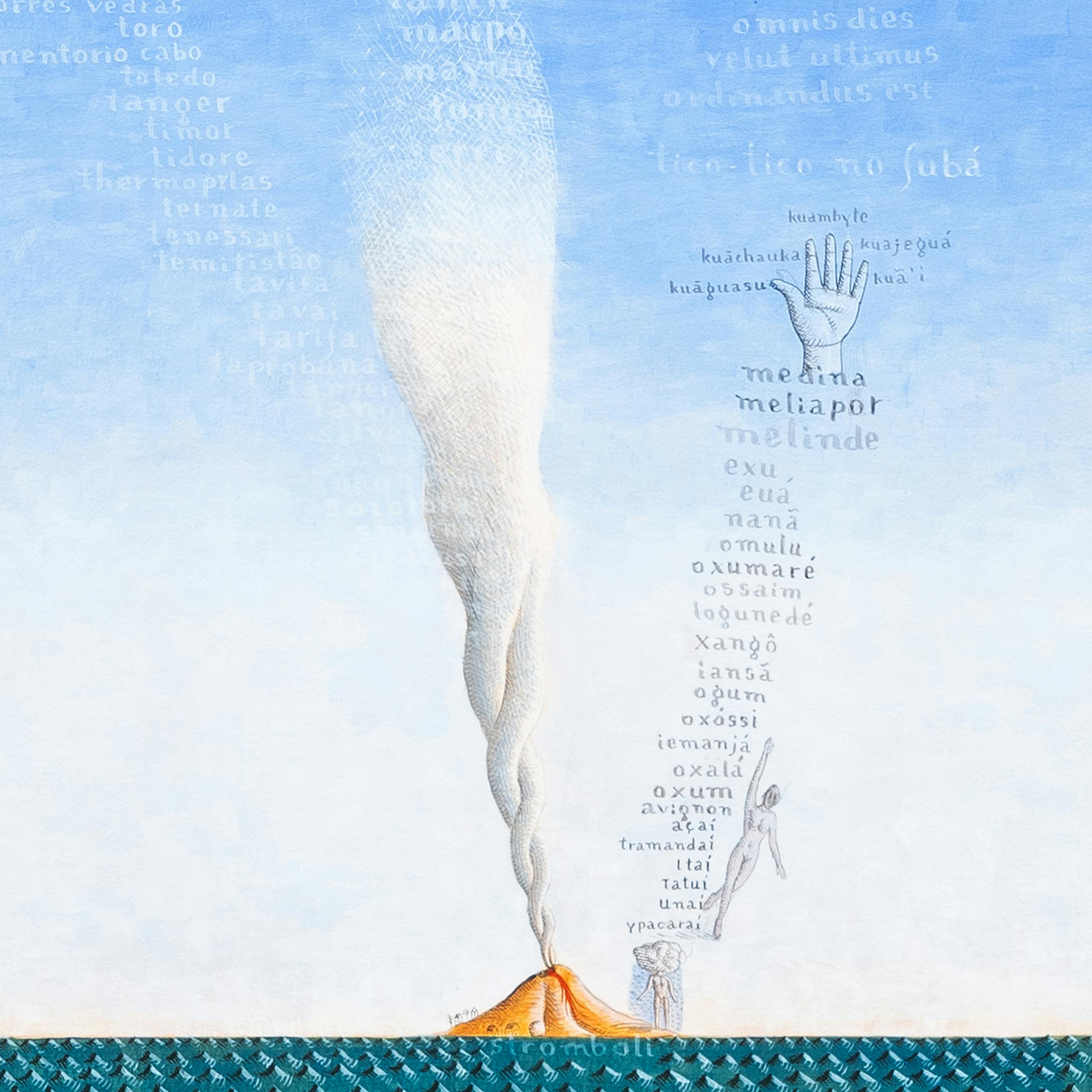

Voci dal Mondo Reale is an original performance that traces a line from the Caucasus to the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, with Italy as the central stage. Fondation Cartier pour l'art contemporain dialogues with musician and composer Alexis Paul and choreographer Alessandro Sciarroni—Golden Lion winner at the Venice Biennale and associate artist of Triennale Milano Teatro—on traditional songs that speak of love, nature, exile and resistance.

How did Voci Dal Mondo Reale come about?

Alexis Paul: After the first time we worked together in 2019, the Nomadic Nights (Soirées Nomades) reached out again saying they wanted to organize an event with choirs and traditional music as part of the Fondation Cartier’s Mondo Reale exhibition at Triennale Milano. As part of my contemporary work involves collecting and updating perceptions of popular culture, I immediately thought of filling Triennale with human voices.

Alessandro Sciarroni: We were privileged enough to put on Save the Last Dance for Me at the Fondation Cartier in Paris, as part of the Damien Hirst exhibition. The aim of the show was to revive an all but forgotten Italian folk dance, the polka chinata. As I’m interested in folk dancing, the Foundation’s curators asked me to collaborate with Alexis Paul in creating Voci dal Mondo Reale.

Alexis Paul, ph. Jérôme Moreau

You are a musician/composer and a choreographer. This was the first time you’ve worked together: how did it go? How did you combine your respective disciplines—music and dance— in order to complete this project, which was created specially for the 23rd International Exhibition?

AP: It was the idea of the Nomadic Nights team: they thought it made sense for us to work together. And actually, we soon realized we had a lot in common; for example, we both believe in repeating and perpetuating certain traditions. There were two phases to the project: first we worked on the music programme, then on the staging.

AS: It was a very gradual process. It’s the first time I’ve ever agreed to organize an event. As usual, I didn’t want to tackle the material we were meant to be working on right away. I decided to wait a long time before venturing into Alexis’s musical universe. It was my job to coordinate the movement of the human body in time and space as part of a system we call “choreography”, but as far as I’m concerned, it’s no different whatsoever from what is more traditionally known as “dance.”

Tell us about your interest in folk music and dancing: what does it mean to you? Why is it an interesting medium to work with?

AP: The concept of art as an instrument and not a destination is central to my work. What I like about folk music is that it’s not entertainment, it’s not for an audience. It’s the music of “ordinary” people, of everyday life; it’s about spiritual expression and nature. Folk music creates a different, more intuitive way of perceiving the world and reminds us what oral cultures have contributed to collective knowledge. Whether sacred or profane, it reveals a dimension that is ritualized but at the same time spontaneous and expresses the human condition in a very direct way: it’s the most beautiful way of illustrating it. While it would have been a problem for me to present this music as a straightforward show, I found it exciting and challenging to express it in an off-beat, creative way, as we did for this edition of the Nomadic Nights.

AS: Folk dancing—dancing in general—is part of human behaviour. The older it is, the more evocative it is of human beings today.

Tell us about these folk choirs: what are the songs about?

AP: Most of our guest performers will be singing songs from the oral tradition, so they’re impossible to date. The subject matter is very varied, as life itself, and it’s constantly changing. Some songs describe or celebrate a specific situation—work songs, celebratory songs, rituals, birthdays, lullabies, hymns—while others refer, in a roundabout way, to feelings or intuitions, to love, exile, etc. And some are resistance songs or odes to nature. But what they all have in common is that they express people’s imagination, with their language and the sense of their physical surroundings. What’s really important about these repertoires is that they are passed down collectively: the individual who performs them takes something of a backseat. The performer may give them a contemporary take, but they’re not original compositions.

What does the title, which was taken from the Fondation Cartier show, mean to you? What are the “voices from the real world”?

AS: Many of the pieces of music we chose for the event were composed centuries ago, and yet they’ve survived until now! As such, they’re our link to the voices of the past. It’s an anthropological approach.

AP: “Voices from the real world” could be the voices we forget or that have practically died out, either because they don’t sit well with the cultural propaganda of a particular government, or because they are no longer passed down to present generations, or simply because little is known or understood about them. And yet, they’re still there: in the valleys and mountains and homes. I like the archaeological analogy: creating something new and surprising with debris is a very powerful concept. That’s what we’re trying to do. Also, people have always celebrated nature through songs or expressed their feelings through their surroundings, so voices from the real world are also the voices of nature, indivisible but made up of many. And those songs from disputed territories or countries that are no longer recognized nation-states force us, by their very existence, to rethink geography, to rethink the World.