Makunaimî devolve a Muirakitã ao centro da terra, 2019. Photo Filipe Berndt, courtesy Galeria Jaider Esbell de Arte Indígena Contemporânea

In Jaider Esbell’s works featured in Mondo Reale, we move between semi-figurative to narrative groups of forms to more abstract, evocative narratives that take us from the microcosm to the macrocosm. Between spiritual and historical visions, Esbell’s work is first of all the result of his multifaceted social engagement as a thinker and his work speaks for itself, bearing the stories of the community he engages with, the Macuxi. Esbell’s research combines intersectional discussions between art, ancestry, spirituality, history, memory, politics and ecology. The use of art as a form of pedagogical activism aimed at amplifying the voice of his own indigenous group and others. We present an original text by the indigenous artist.

Aprendendo os segredos das águas, 2013, photo Marcelo Camacho, courtesy Galeria Jaider Esbell de Arte Indígena Contemporânea

Lexicon for explaining “permundos”: how can the entity indigenous artist “fish” in two waters of the same lake and serve two communities?

Lexicon for [explaining] “permundos” is a proposal I bring. They are non-places, requiring their own dictionary – but is that even appropriate? What we know is that in our present days and age a specific living being exists, one identified as such by people with little to no sensitivity who pursue creators of unusual content.

These living beings are dispersed and can be seen – barely – as an outline in the few pockets of surviving forests; watered down in the vast, open, and peripheral waters of our media. Science ignores them, adopting the narrative espoused by these lazy filters.

And so here we are, today, when we can dream of disseminating their lives, getting to know them, and realise we have fallen under their spell, enamoured by their resilience. Their insistence in standing up to a society which wishes to remove whatever strays from “normalcy”. Beings who have been shaped, for centuries, by other entities, preaching their memories rather than sticking to the real or official history.

They are artists, even though they are greatly discredited by pioneering expropriators thinkers, those who determine whose name can be added to buildings and facades, consumed and gazed at by green and blue eyes.

They are thinkers who use their bodies as a projection to live in other lives, which have always been there, but who signal their presence on this side of the lake by means of their essential energies. They express their contents, an inextinguishable source of their identity, a tangible body which goes beyond any form of understanding.

Today, these artists exist. They flee. They settle down. Some do it exceedingly well. They leave their original places to expand their connections like fish which, when their lake runs dry, flop on dry land for miles until they reach another body of water to continue their journey.

A trip which wasn’t undertaken by these modern artists, but by their very first forebears. And yet these people, today, are called to continue the journey, despite the potential bodies of water are becoming scarcer and lie further and further apart. Distances and scarcity are a “contemporary” element – after all, this is a post-everything era.

However, the word is still useful. There are still traces thereof, and just about enough light to analyse it under this perspective.

Indigenous artists, nature’s elementals, swim in the double, choppy waters of misunderstandings. They have to wade across lakes and, therefore, move.

Their movements cause bizarre ripples – a disturbance in the water which, up until this day, was circumscribed to the communities. But something has changed – it is palpable. We ask ourselves: what do they want? Can they move freely without us? Why do these beings, who come from another world, want to meddle in our affairs? And the same questions echo within the communities from the other side of the lake.

These deviants only have ears for their ancestral voices and put a lot of work in fishing in these double waters to serve moquéns, damuridas, and other types of broth, forgoing the traditional feijao com arroz with such aplomb that diners do not even notice the trick happening under their eyes.

Then comes the second emotion/thrill, the diners relish the meals, swept off their feet by their flavours, so much so that they forget to invite the fishermen to join them to the table which keeps on getting bigger.

Complaints have no place at this table. If you are art, you know where you stand, and these places are just for them, busy occupying the social roles of the many communities they derive from self-exhaustion.

Once people said other worlds existed, they brought his claim with them, these needs, a violable involution, made to be seen. A contagious one spreading creativity. Upon seeing it, and taking it within themselves, they will shine.

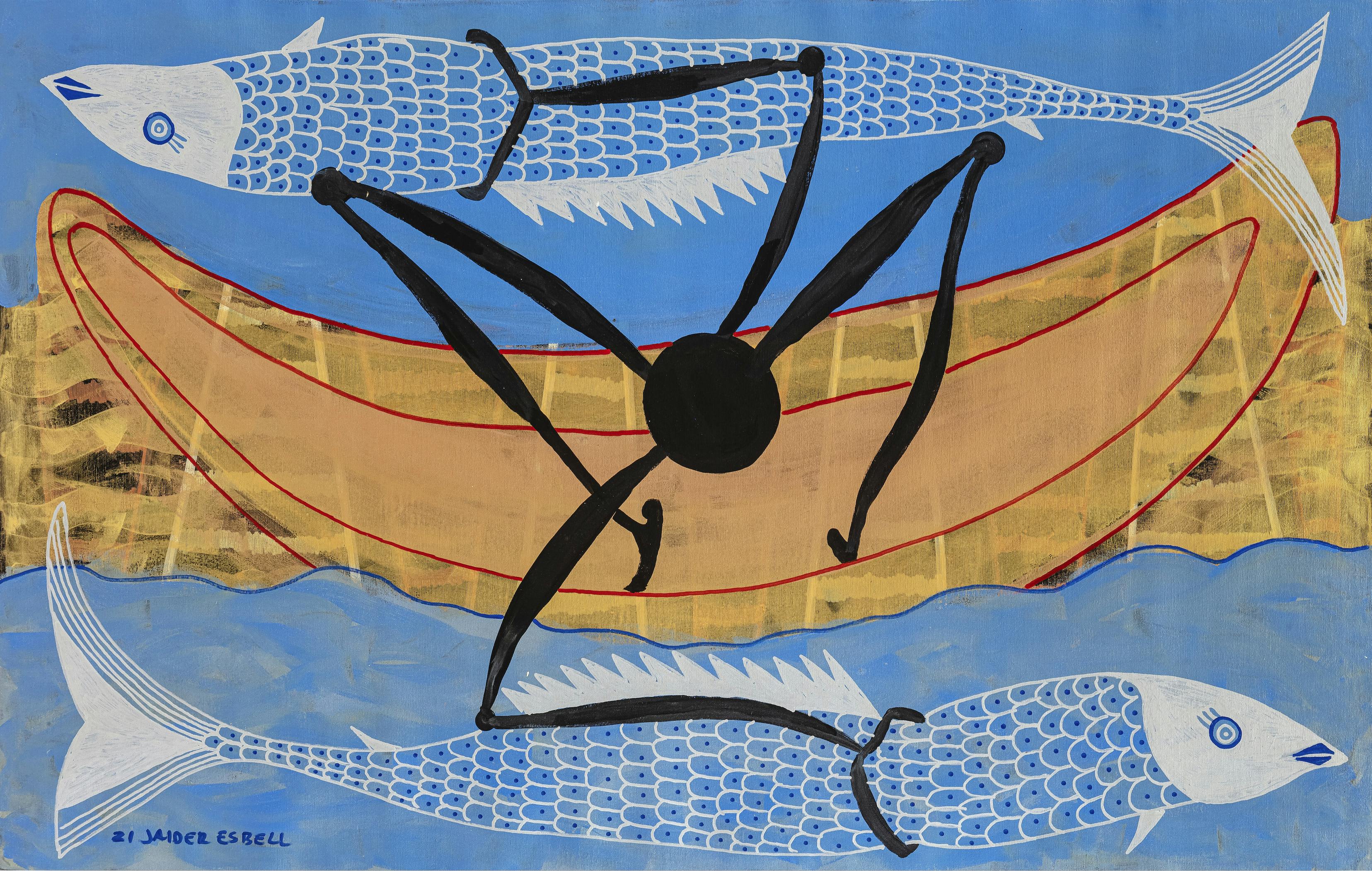

Entre o ar e o mar – pescaria e oferenda, 2021, photo Filipe Berndt, courtesy Galeria Jaider Esbell de Arte Indígena Contemporânea

Credits

Léxico para permundos: Como a entidade artista indígena pode “pescar” em duas águas e servir a duplas comunidades? Originally published on 16/07/2020 on the artist’s blog. Available on: http://www.jaideresbell.com.br/site/2020/07/16/lexico-para-permundos-como-a-entidade-artista-indigena-pode-pescar-em-duas-aguas-e-servir-a-duplas-comunidades/

Related events