Hidden Technology

October 28 2022, 4.30pm

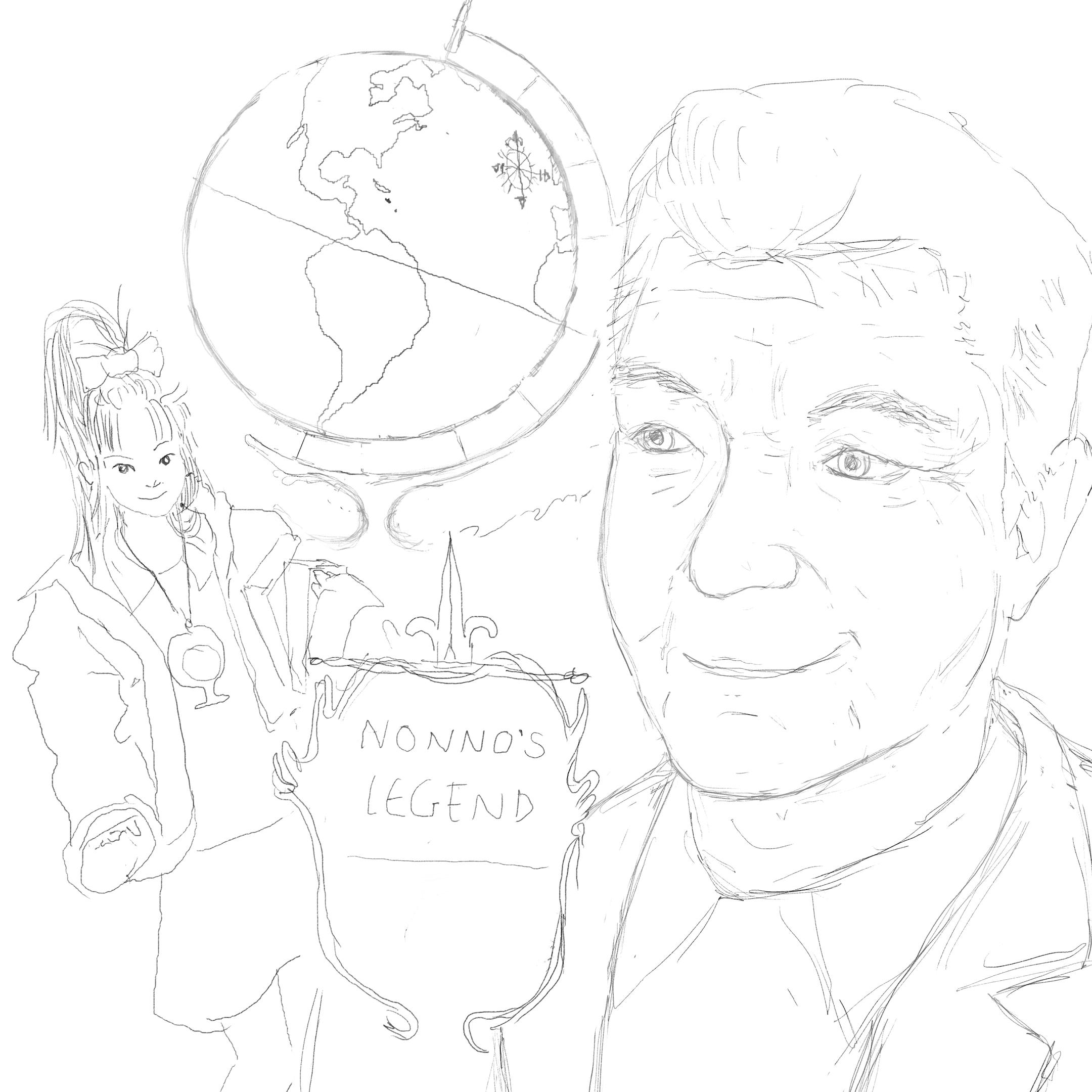

Nonno's Legend, frame. Courtesy of the artist

As part of Game Collection Vol. 2, a virtual exhibition curated by Pietro Righi Riva and presented on the occasion of the 23rd International Exhibition, Giulia Trincardi talks with Nina Freeman and Jake Jefferies of Star Maid Games (USA) about magical globes, family and the unknown.

Among the elements that make up gaming, the imagination is probably the most important. After all, it's possible to play almost without any rules — perhaps just with a physical input, such as jumping, turning around or running; but it's not possible without inventiveness, a process whereby we can immerse ourselves in other worlds and maybe — why not? — establish a dialogue with places, settings and characters that we don't know, but that appear where before there was a void. In other words, imagination may be a key to interpreting the unknown, a practice (as much as the game itself) of free interpretation and creative invention of new worlds, as well as exploring our own identity and history.

As part of the 23rd International Exhibition Unknown Unknowns. An Introduction to Mysteries, with the second edition of the Game Collection curated by Pietro Righi Riva, Triennale Milano is presenting the interactive work Nonno’s Legend, designed by Nina Freeman and Jake Jefferies, which offers the public a magical object — a world globe — to bring about a transformation as delicate in appearance as it is powerful in terms of the imagination. What would happen if we could change the composition of the landmasses and oceans of our planet? What infinite numbers of other planets could we invent, and what stories would we tell about the life on those planets? We spoke about this with the game developers and about the deep bond that the imagination has with the precious figures in our lives.

Nina Freeman, courtesy of the artist

Hi Nina, thanks for joining. How are you?

Nina Freeman: I'm good thanks! This is Jake, who curated the graphics and the more technical development of the game, while I took care of the design and the writing, as well as some of the coding.

It's a pleasure to meet you both! I must ask you something straightaway, because I'm really curious about it: the title of the game is Nonno’s Legend” and “nonno” is an Italian word. Can you tell me why you chose that title?

Nina: The game was very much inspired by my grandfather, who died a few years ago: he was Italian, or rather, he was born in the USA but his father was an Italian immigrant. He always had me call him “nonno” (granddad) and my grandmother was “nonna” (grandma), also in Italian. He was an important part of my life, and when Jake and I were given the Triennale theme and we started thinking about what it meant for us to explore the unknown, I immediately thought about my granddad's old world globe, about how mysterious it was for me to spin it around and stop it with my finger at some random point, and then to imagine what that unknown place was like. When I create a game, I always start from personal experience, and my memories and Jake's passion for designing maps turned out to be the perfect combination.

So the grandfather that we see in the game is actually your granddad?

Nina: Yes! I adored my granddad and I always wanted to create a game dedicated to him. I sent Jake some photos taken at various points in his life and Jake portrayed him in the style of the game.

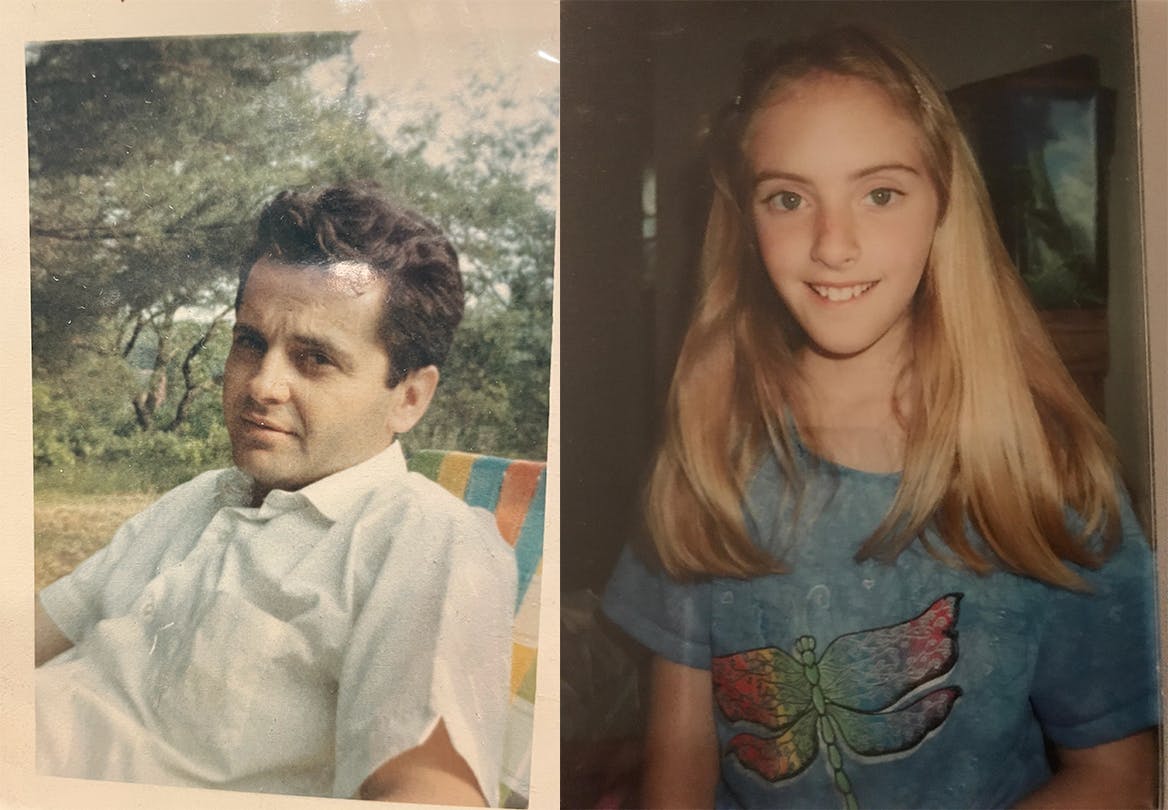

Nina Freeman's granddad as a young man (left) and the designer as a child (right). Jake Jefferies, who designed the graphics for the game, used photos like these to create the characters in Nonno's Legend. Photos by kind permission of Nina Freeman and her family.

Talking about the structure of the game, it seemed to me to be the opposite of a jigsaw puzzle, in a way. When you do a jigsaw puzzle, you are making something following precise rules, whereas in Nonno’s Legend the player “destroys” the actual composition of the continents in a playful way to create something unexpected. How did you arrive at the mechanics for the game?

Nina: Our initial idea actually sprang from that basic action of spinning a globe and stopping it at random. In general, that's how we always work: we start with an idea and develop it in different ways. Jake loves to insert actual elements of physics into the games that we create, often with an element of frivolity, a humorous corporeal element. In this case we had a planet with its continental landmasses and the possibility to make it rotate, so we asked ourselves: how can we make it “frivolous”, evoking a child's spontaneous imagination? That's how the idea came about: for a child it would be fun to take a planet to pieces in order to create their own version of it. Since the theme of the Triennale Milano 23rd International Exhibition is the unknown, we didn't want the Earth to be the only possible planet. So, we decided that the Earth would just be the starting point to work from, from which we would create our own globe using the landmasses that we know, and that are also familiar to a child. After all, a child might think that other unknown planets would look a bit like our own planet, so what would happen if we offered them the tools to design a map of their own?

Jake Jefferies: I adored drawing maps when I was a child; imagining the life on those planets, reading about Jupiter's satellites and so on…

Yes, that's definitely something I used to do as a child, too. And I should think it's a way to lose yourself with the unknown and to make it your own, in a way.

Nina: One thing that was important for us was the physical nature of the globe: it's not an abstract object, but an object that stands on a table, in a room. I remembered my granddad's globe in the living-room very well and Jake had fun imagining how an actual magic globe could be “released” with a magic button.

Nonno's Legend, frame of the game, courtesy of the artist

It's fun to see how the physical nature of the various parts of a “magical” globe can change: that's something we're not used to. For us, the continents don't move: they're unchangeable, even though that's not actually true.

Jake: Yeah, they certainly do move! But they do it very very slowly.

You also chose not to “divide up” the parts of the continents following the country borders that we all know, but instead by following natural boundaries…

Jake: Yes, I studied the maps from a physical and geographical point of view, so I set the fractures where there are rivers and mountains, asking myself: "OK, if I pulled this piece of land very hard, what would happen? How would it break?”

As the proud daughter of two geologists, I certainly appreciate your choice. Nina, you spoke of your granddad as a great story-teller and someone who has always inspired you. Is there any particular story or “legend” that he told you that you can remember?

Nina: Talking about the word “legend”, the title of the game is a play on words: in English 'legend' can mean story or myth, but it also refers to the instructions for reading a map.

That's true – I hadn't noticed that!

It's funny, because the game doesn't actually have any legend in the sense of instructions. My granddad was an incredible person: the most vivid memory that I have of him is that in our family he was the person most like a teacher, even though that was never his job. He really wanted me to learn the right spelling of words, and he taught me lots of words. The first word he taught me was “mandria” in Italian ("herd"). Don't ask me why! He had a great passion for food and I remember that he wanted me to learn the word “milk” and I was sitting there at the kitchen table with him, writing the word “milk” again and again. I remember the beautiful tiles on the floor, and the colored windows that one of his artisan friends made. His house was always full of food and art. He wanted me to be good with words, and it's funny because now writing is what I do for my job, and I like to think that it was all because of him: that it all started with my granddad teaching me how to write “milk.”

And how about the globe?

My granddad didn't have a particularly large house, but he loved books, so he had converted a storage space at the end of the living-room into a little library, with shelves of books from floor to ceiling, and that was the space where there was the table with the globe on it. He was a man who loved words.

One of the preliminary sketches for Nonno's Legend created by Jake Jefferies. Image by kind permission of the creator and Nina Freeman.

You mentioned the fact that “legend” means both “legend” as in myth or story, and “legend” in the sense of instructions, and in the end those are both things that help us to organize what we don't know. What relationship do you, as designers, have with the unknown?

Nina: It's funny because in a way the unknown seems to be where my interests meet Jake's. We both used to develop games separately before we met, and I have always created things that are strongly linked to my personal life — the people that I've collaborated with over the years have always patiently accepted that that was my way of doing things. I have a background in literature and poetry, and my favorite authors write about their lives, about real experiences. Whereas Jake is more attracted to fantasy, and exploring ideas from different worlds. I wanted this game to be a meeting point between the two of us and I asked myself if there could be a magical element in my actual memories. So, we created our globe that detaches itself from its axis, rotates in all directions, and has continents that move around… it's definitely the meeting point between our interests.

Jake: I think the same, and I must add that from the engineering and artistic points of view, the unknown often happens when you develop a game, because you have an initial idea of what you want, but you don't know how to achieve it and you have to find that out and find the tools to create it. It often happens during the design process that you venture into the creative unknown.

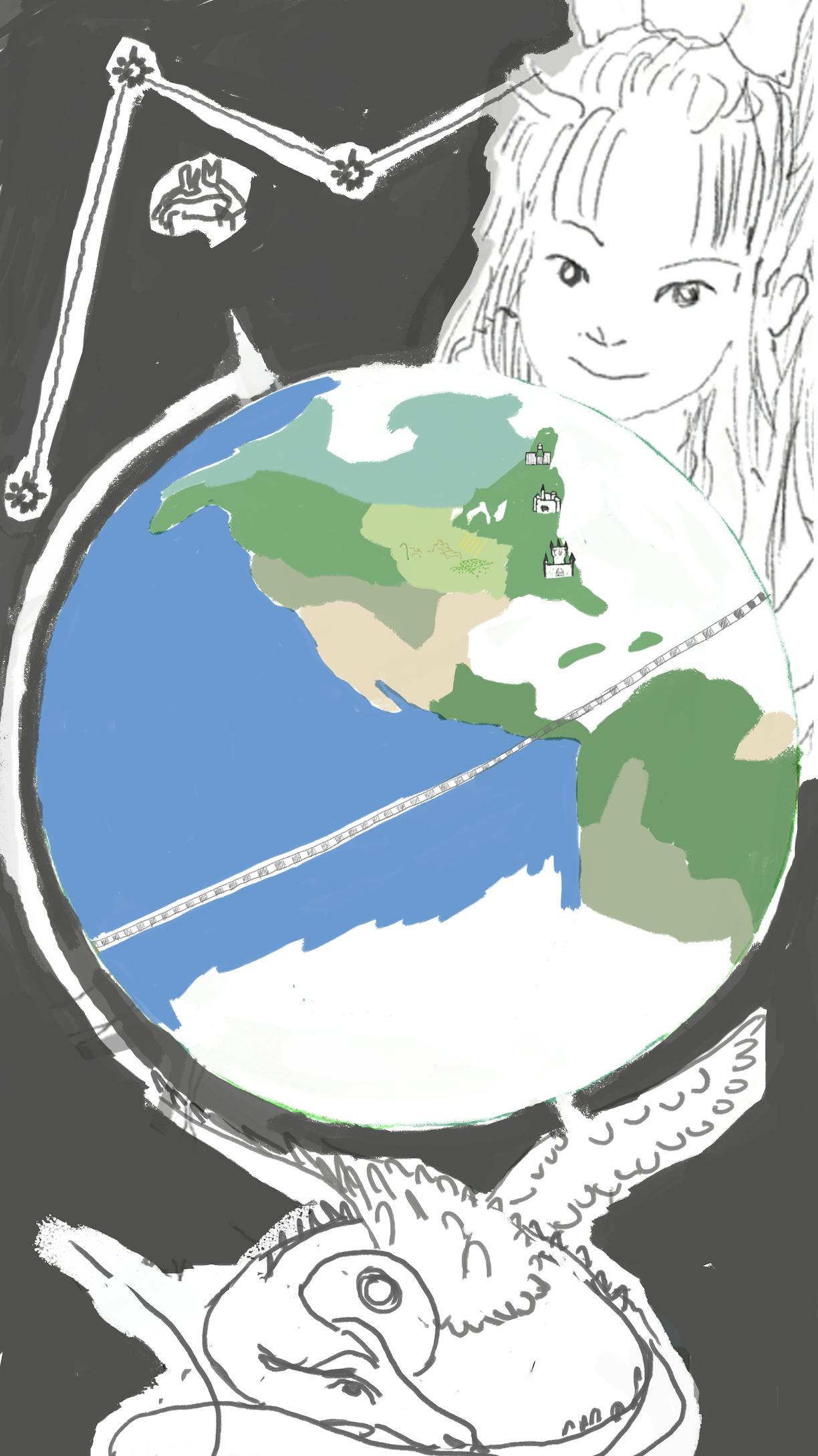

A color sketch of the globe from Nonno's Legend and of the main character inspired by Nina Freeman. Image by kind permission of Jake Jefferies and Nina Freeman.

Does it ever happen to you that you write a piece of code that works, but you have no idea why it works?

Nina (laughing): Oh yes, absolutely.

Jake: Does it ever?! Sometimes I say to myself: “OK, I know that this shouldn't work and yet it does work, so I have to understand why.” And at that point I spend ages racking my brain to find out what I did.

Nina: Nonno’s Legend is much more complex than it appears. It's a simple game, but the conversion of the globe from a 2D map required a lot of work. There's a lot of depth in a game that appears quite simple: a multitude of invisible layers.

When you think about the unknown, is there something that gives you comfort? That makes you think: “OK, in the end that's all fine”?

Nina: I think that especially when you're very young and there's still so much to learn and the unknown appears deeper than ever, gaming — just the activity in itself — helps to manage these feelings. For example, when you spin a globe and put your finger on a place you've never been to and perhaps will never see, in a way, you take a little piece of it, because it's imagined as you want it to be. And in the end, even as adults, we continue to do that: to play and to imagine.

Jake: We certainly do, and still with maps, too. We play GeoGuessr a lot, for example.

Ah I love GeoGuessr! It's one of my all-time favorite games.

Jake: When I was studying the maps for Nonno’s Legend, I spent loads of time researching on GeoGuessr.

Nina: It's so much fun! We both play a lot of games as adults, too, and both of us use gaming to develop complex aspects of our lives and our characters. We haven't travelled much over the last few years for obvious reasons — and this game gives us a really interesting sense of freedom.

I feel the same. It lets you escape, and explore unknown places.

Nina: For me, exploring a map and talking about the unknown is still a practical issue: the theme of the Game Collection perhaps makes you think first about the unknown in the sense of deep space, of what lies beyond our limited perception; but for me, as someone who is mainly interested in the everyday, when I'm asked to think about Space, the first thing that comes into my mind is a physical, concrete space: a table with a globe on it. My instinct is always to contextualize concepts that are bigger than me in the everyday, because that's how I think about the world; it helps me to feel connected to a concept.

On the other hand, we know almost nothing about macroscopic stuff and almost nothing about microscopic stuff — it's very human to stay “in the middle”, in one dimension: it makes sense for us as human beings. You know, talking about the map in the game, I tried to move all the landmasses towards the poles, so I could have an enormous ocean in the middle. What “new world” configuration in the game made you say: “OK, this is really the best!”?

Jake: I love creating fantasy maps as a hobby, and one thing I liked to do when I was testing the game was to mix up the continents just a little, but to turn the axes radically, so that for example the tip of South America ended up on the Equator and the North Pole was no longer in the north, but instead there was central China or Europe in its place — and I had fun imagining the implications of a change like that, because the world would be very different. And even though that isn't the point of the game, it's inevitably something we think about.

I have a question about that specific point. Nonno’s Legend isn't a political game in the narrow sense of the word and it has a very relaxing element just because there are no political boundaries on the map, and in “re-shaping” the world, you don't do it with the same intentions and consequences that drove European colonialism, for example. What are your thoughts on that?

Nina: When we were testing the game, people asked us if it was a game linked to climate change, and to the future consequences that will convulse the world. Obviously, that's one thing we thought about, just as we thought about national borders and how they change, and what led to them changing through history.

But the game is designed from the perspective of a child — and as a child, I didn't know what countries looked like; I had seen maps, of course, but I hadn't internalized the borders between one country and another, or what they meant. So I thought: “How would I look at the world as a child, to play with it?” I wouldn't look at borders, but just at their natural shapes. In any case, Nonno’s Legend will be played by people all around the world and we don't know what they might think about the political borders in the places where they live. I didn't want to be an opinionated American saying “Ah, there's a boundary here”: I didn't want to take anything for granted. So, we chose to represent it physically, based on mountains and rivers…

Jake: …but not in a way that was too realistic either, because that could also make you think about political borders. It's more a kind of playful representation, as though it were a world made out of scraps of paper.

Nina: Although the world of the game is based on the Earth, the point is to create something new and unexpected, that could be an expression of a different planet. The Earth is only the creative template. Wondering about what would happen if it were really possible to change a planet like that lies in the imagination of the person playing. It's interesting that some people think about it in a literal way, and the difference between how adults and children think was one of our considerations.

A sketch with details of the globe from Nonno's Legend. Image by kind permission of Jake Jefferies and Nina Freeman.

Do you think that people would react with a sense of relief if they actually saw a map that was completely different from what we know? Or do you think it would just be chaos, because we would find ourselves somewhere else on the globe, with a different climate and so on…

Nina: I think it depends a lot on the person. Some may play it and say “Oh, it makes me think about the climate crisis.” When you have the planet as a canvas, it's easy to bring real problems to the surface — people might think of their own country and of what would happen if you moved it — but that all becomes part of their creative process. And that's why it was important for us that it was playful and not “serious”, and that it didn't have too many rules to follow.

Jake: It's difficult to say how people would react if something like that happened in real life. How would we decide to attribute different functions to the concentration of landmasses? What land would we cultivate? I think the distribution between North and South would be very important, for example. But also, would we be free to choose where to live? I don't know; the most likely outcome would probably be chaos.

Nina: We watch a lot of documentaries about how animals or plants are found in different parts of the world because they moved at various times in history because the continents moved. So, there's a precedent, in a way, in the history of the evolution of life. Only it was much slower, as we said earlier.

The game's graphics remind me of the illustrated books I used to read as a kid. Were you inspired by anything in particular?

Jake: We started from photos of Nina. As an artist, I obviously have references buried deep in my mind: if I had to name one for you, it would perhaps be Eloise [a character created by the American illustrator Hilary Knight], because Nina has something of that smart, sassy look in the drawings.

Nina: I gave Jake photos of me as a child and photos of my granddad, but we wanted the visual part to be in line with the imaginary world and the childlike energy of the game. I work with Jake for many reasons — we're married and that definitely helps! — but I love his style. Our process often consists of: “Jake, draw anything you think is fun to draw"; and we spend months, if not years, working on a game, so it's important to work with a style that we find pleasant and enjoyable.

How do you think your granddad would react to this game?

When we began working on the game, after we received the invitation from Triennale, I was really thrilled at the idea of being invited to take part in a project developed in Italy, because my granddad was so proud of his roots, and that pushed me to find out more about my own roots. I know that he would be proud of me and this was a strong motivation for me when I was working on Nonno’s Legend.