Courtesy Inga Sempé

A designer’s work is made of full moments and empty ones, of long waits and frantic searches for the “right” solution, the one that reconciles form and function without one overwhelming the other. The French designer, whose work is celebrated in the “imperfect house” set up in the Design Platform space, told us how one of her latest creations came about.

Courtesy Inga Sempé

Courtesy Inga Sempé

Over the last few months, I had a chance to talk with Inga Sempé on several occasions via a telematic cable connecting Milan with her studio in the 10th arrondissement of Paris, a stone’s throw from the Canal Saint-Martin. One thing I noticed is how much the French designer loves to show what, in her language, is called “l’envers du décor”: the behind-the-scenes of her projects, but also the small imperfections and elements of discontinuity hidden behind the glossy facade of things. She did just that, in fact, with the force of a manifesto, designing the exhibition of her work, Inga Sempé. La casa imperfetta, along with Marco Ammicheli. There, furniture and objects designed over twenty years come down from the pedestal on which we are accustomed to admiring them, at least in a museum-type context, to take their place in a domestic interior meticulously recreated, even including traces of its inhabitants’ presence, from a shopping list scrawled on a whiteboard to burned-down candles.

Courtesy Inga Sempé

Courtesy Inga Sempé

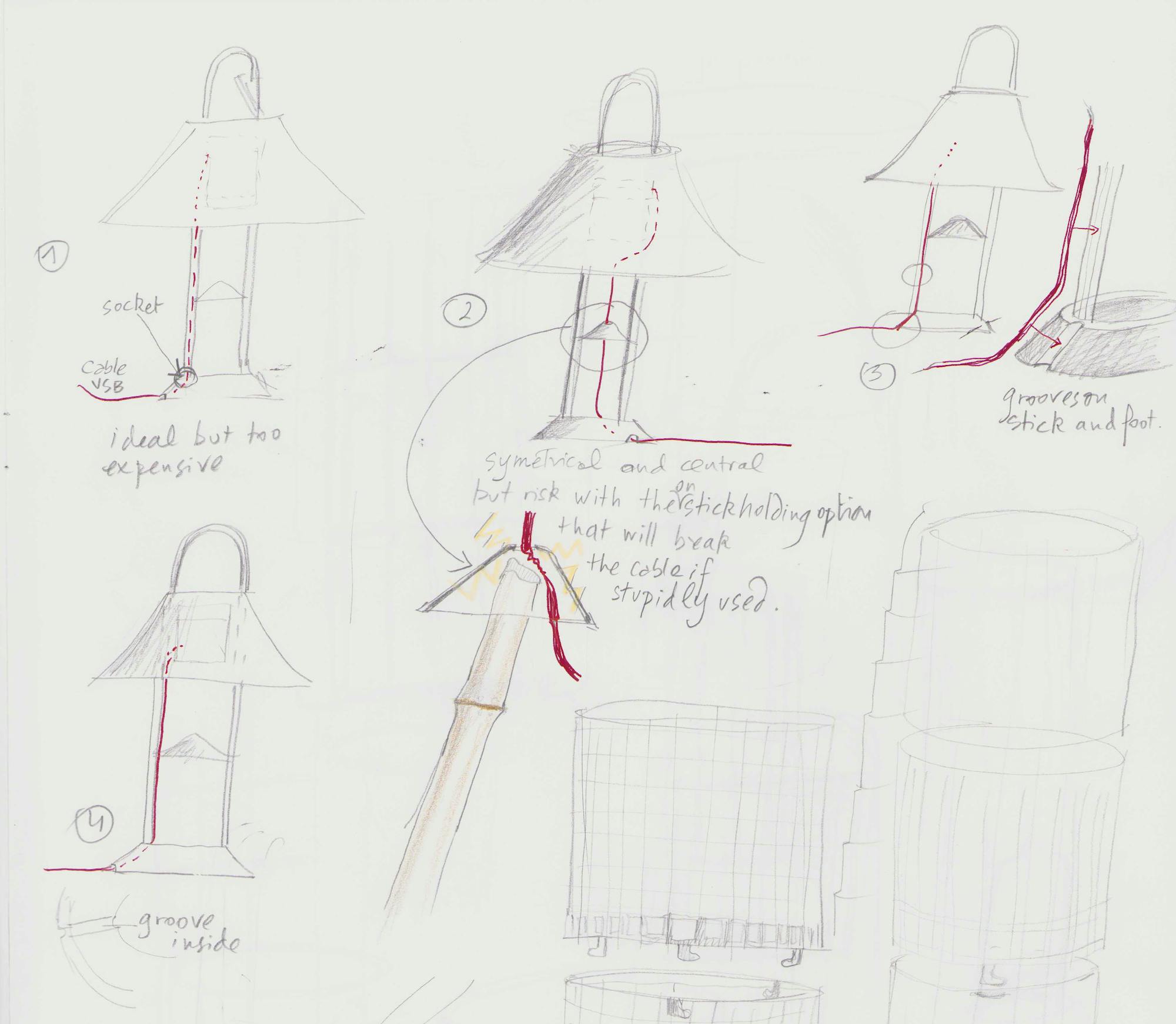

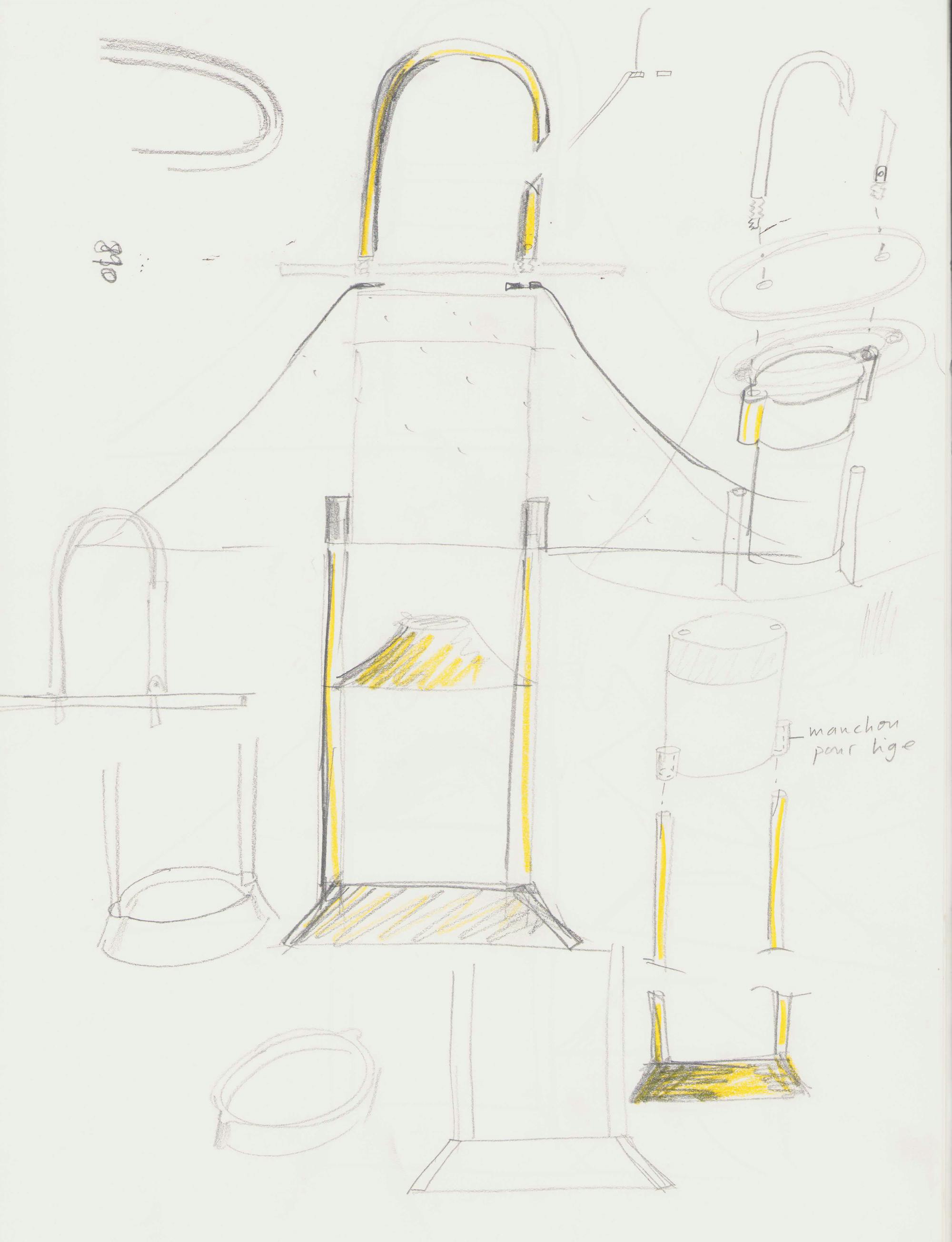

One time I asked her to retrace the main phases of her creative process for me and the readers of this magazine using the example of a recent project – the portable Mousqueton lamp, made last year for the Danish company Hay. In her typical style, she did not try to minimize the missed steps and difficulties encountered along the way. “I received the brief in April 2020, right at the beginning of lockdown,” she recounted. “It was a battery-powered lamp and, although it wasn’t clearly indicated, I immediately thought that it must be an outdoor lamp, as sturdy as military equipment so it could be used without too many precautions, even in the wild. My goal was to make it possible to hang the lamp from the branch of a tree or from a rope suspended between two points, or set it on a stick planted in the ground to shed light on a picnic. I spent the next six months chasing after the right idea, making drawings and models that I threw away almost immediately – and baking cakes, like almost everyone during lockdown.” Daughter of two artists – the renowned illustrator Jean-Jacques Sempé and the Danish painter Mette Ivers – Inga never believed in the myth of inspiration that appears suddenly from who knows where. On the contrary, she was taught from a young age that creativity, in whatever form it appears, is necessarily the result of multiple attempts and a great deal of effort.

Courtesy Inga Sempé

Courtesy Inga Sempé

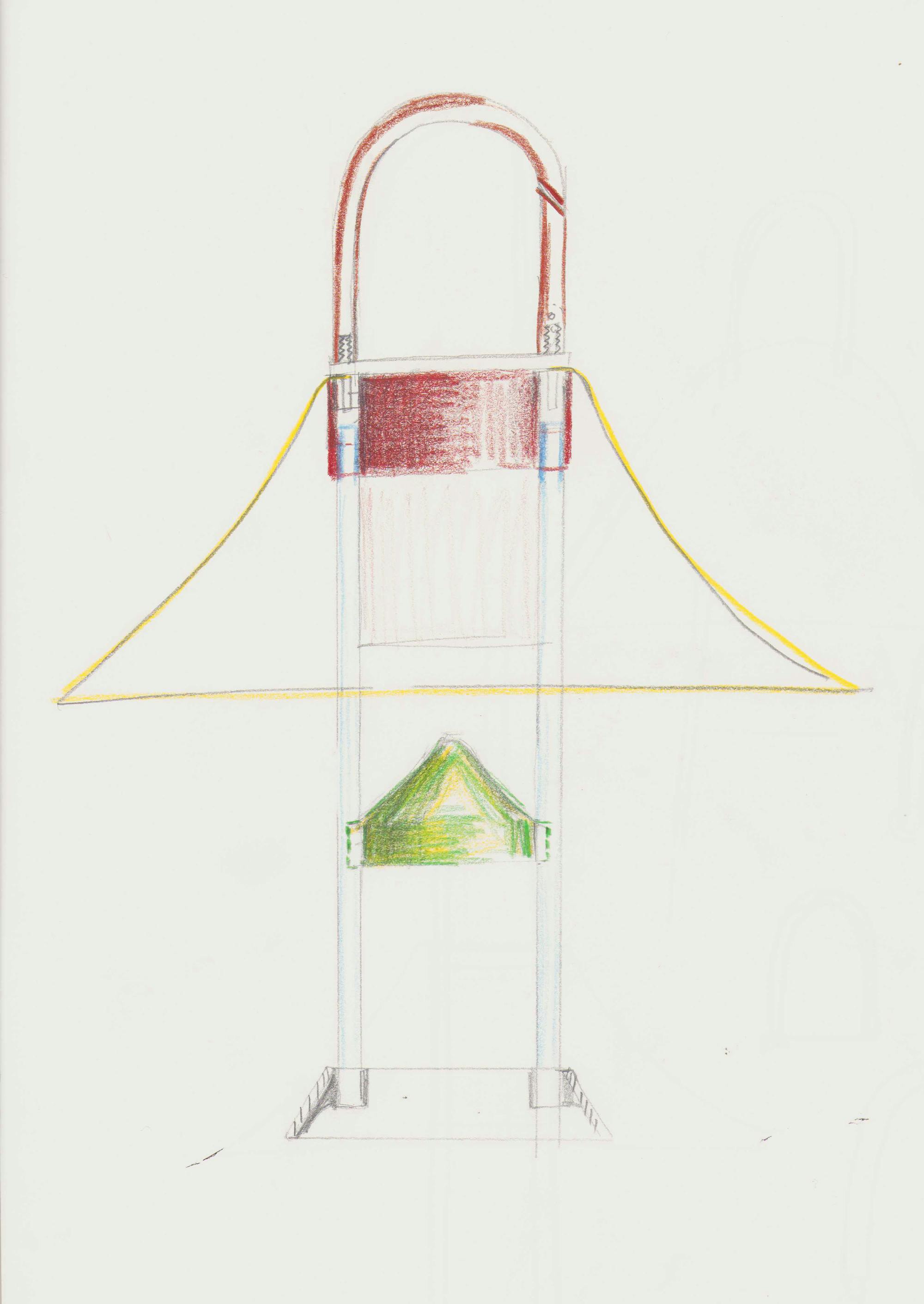

As its name suggests, Mousqueton’s metallic structure traces that of a carabiner, a metal clip with one end that opens, used, for example, by mountain climbers to secure ropes to supports anchored in the wall. “I understood that this solution was the right one because it is easy to use and it opens and closes, allowing the lamp to be hung from a support without an open end, which would have been impossible with a standard ring hook,” she explained. “I wanted to give the user as much freedom as possible. The carabiner, however, also gave us a number of headaches. It was still too laborious to release or, conversely, too weak. We experimented with different opening mechanisms, upwards and sideways, and eventually chose the latter because it allowed us to attach the lamp to branches or ropes with a larger diameter.” Meanwhile, a cone-shaped reflector positioned halfway between the base and the lampshade allows both a softer diffusion of light and the possibility of securing the lamp to a pole as the designer wanted. “It was important that this system not be noticeable when the lamp was used in other ways. In general, I know I have found the right idea when the function cannot be seen, when it disappears behind an apparent lightness.”

"In general, I know I have found the right idea when the function cannot be seen, when it disappears behind an apparent lightness.”

Two and a half years passed between the first sketches of Mousqueton and its release, a rather long period marked by trial and error, by numerous adjustments and the constant coming and going of packages with models and prototypes between the Hay headquarters in central Jutland and the center of Paris. Even so, the three colors of the lampshade – white, steel and a brownish-red – were only settled on later, after studying a long series of alternatives ranging from blue to the many shades of green typical of garden furniture. “This type of process is completely normal,” Inga explained. “There are almost always technical or economic impossibilities that force us to rework a product, details to revise according to instructions provided by the company, small problems that seem huge at the time but are forgotten as soon as they are resolved. In the studio, we are often working on five or six projects at the same time, and each one has ramifications that can bear fruit at different times.”

Courtesy Inga Sempé

Related events