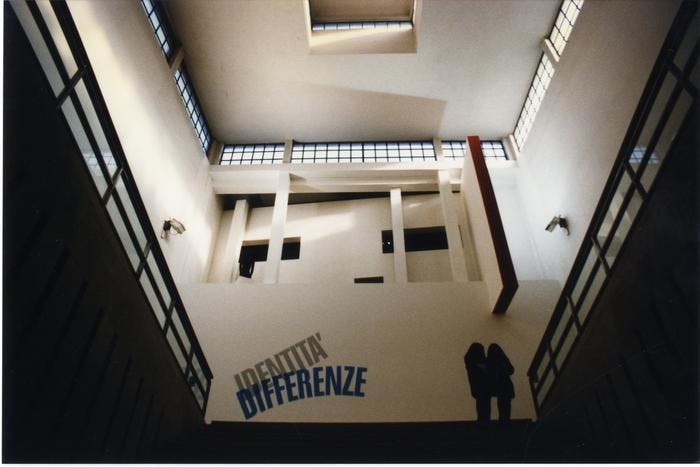

19th Triennale, exhibition Gli immaginari della differenza, Arazzo, aria, rete project by Juan Navarro Baldeweg

After almost thirty years, two contributions from the catalogue of the 19th Triennale in 1996, Identità e differenze (Identity and differences), show similarities with the themes of this year's 24th edition: Inequalities.

During its first century of activity, Triennale Milano has produced a vast archive of cultural resources which, with the distance of time, continues to raise questions and spur reflection. In this article I wish to retrieve two contributions – one by architect Ignasi de Solà-Morales and one by sociologist Bianca Beccalli – from the catalogue for the 19th Triennale in 1996: Identità e differenze. From a distance of almost thirty years, these articles show similarities with the themes of this year's 24th edition: Inequalities.

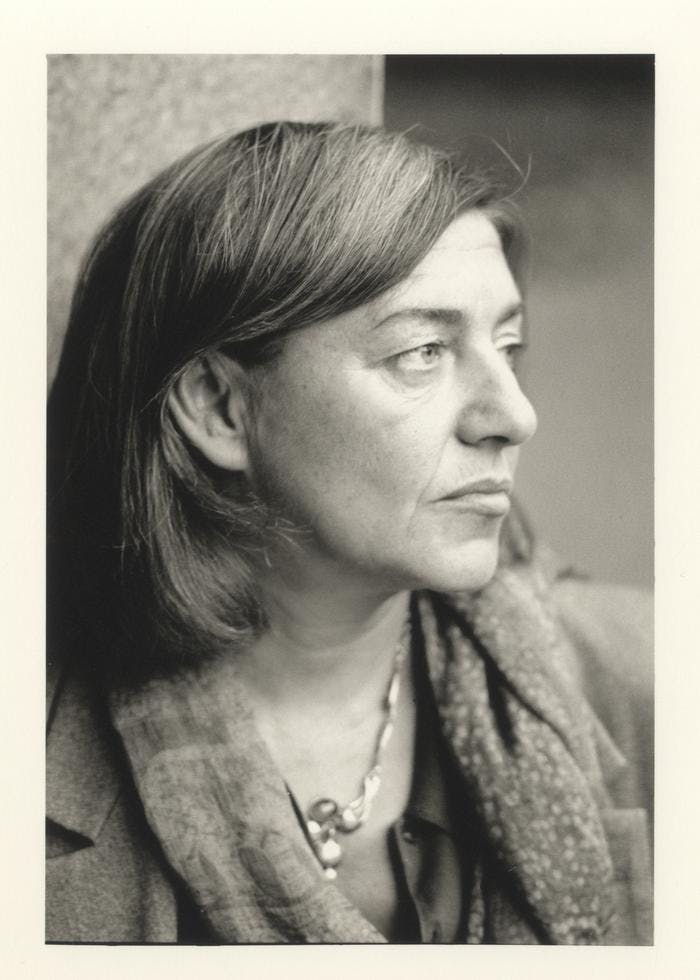

19th Triennale, Bianca Beccalli

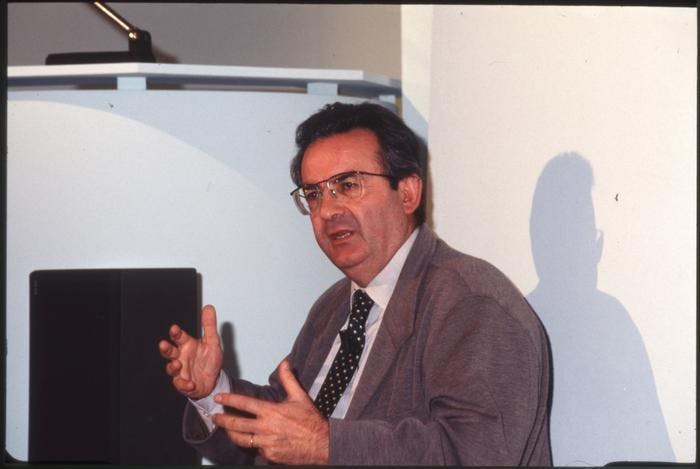

19th Triennale, Ignasi de Solà-Morales

19th Triennale, Ignasi de Solà-Morales e Bianca Beccalli

“The Triennale board of directors has chosen this theme for the 1996 International Exhibition in the awareness that this broad and complex range of issues lies at the basis of the key problems of daily life all round the world. Recognition of our own and others' identities, and respect and understanding of our differences, are necessary conditions for us to live together in a peaceful and civilized manner.” It was with these words that the then president of the board, Pierantonino Bertè, described some of the aims of the 19th Triennale, interpreting the general feeling that saw architecture and design as the tools for the peaceful resolution of conflict. However, de Solà-Morales's contribution to the catalogue immediately appears to be a criticism of this stance, beginning as follows:

“The usual interpretations that have been applied to modern architecture tend to promote the idea that a work of architecture represents peace-making. Social problems, indigenous cultures, the built historic heritage or nature: architecture seems to have been called upon to resolve all these contradictions. A judgment on the quality of the architecture seems inescapably linked to its ability to represent a conciliating response.”

19th Triennale, International participations, exhibition design by Hermann Czech, Scalone d'Onore, Triennale

19th Triennale, exhibition Gli immaginari della differenza, Pulp city project by Craig Hodgetts & Ming Fung

For Solà-Morales, by contrast, architecture is always “a violent act”, linked to the dynamics of power aimed at control. The text describes the relationship between architecture and two systems of power: colonial and neocolonial. In the colonialist phase, domination was carried out with violence and by means of closed architectures, designed to isolate and control people – as Foucault also describes. But de Solà-Morales expands on this concept: “Architecture, like colonialization, is also a violent act. There is no point in hiding the central dimension of every construction operation. When we construct, we destroy, so it is absolutely illusory to think that the action of architecture on a territory is an action in harmony with the apparent and universal order of things."

The Foucaultian closing of institutions is transformed into a control that is remote, abstract and not localized

With the fall of the colonial empires after the Second World War, a new type of control began to spread, however: “We passed from colonial military domination to financial and economic domination, in such a way that the machinery of power no longer needed to be opaque physical structures but could develop through transparency and dematerialization. [...] The new configuration of domination is represented by architecture that is open, brilliant, transparent, interconnected, mediated by corporations, bank headquarters and information screens displaying abstract share values. The Foucaultian closing of institutions is transformed into a control that is remote, abstract and not localized.”

Cities, 24th International Exhibition Inequalities, 2025, photo by DLS Studio

Cities, 24th International Exhibition Inequalities, 2025, photo by DLS Studio

Even if the architecture of power is changing, the detrimental effects that it continues to produce in colonized territories do not change; examples of this are still evident today, as shown in the Inequalities exhibition. In Cities, for example, Andrés Jaque shows how the skyscrapers in Hudson Yards, Manhattan owe their glossy sheen to titanium extracted from Xolobeni, in South Africa, where the mining makes the sandy soil light and unstable, impeding the cultivation and livability of the area: the absence of dust on the buildings of power leads to a lethal dust on the other side of the world.

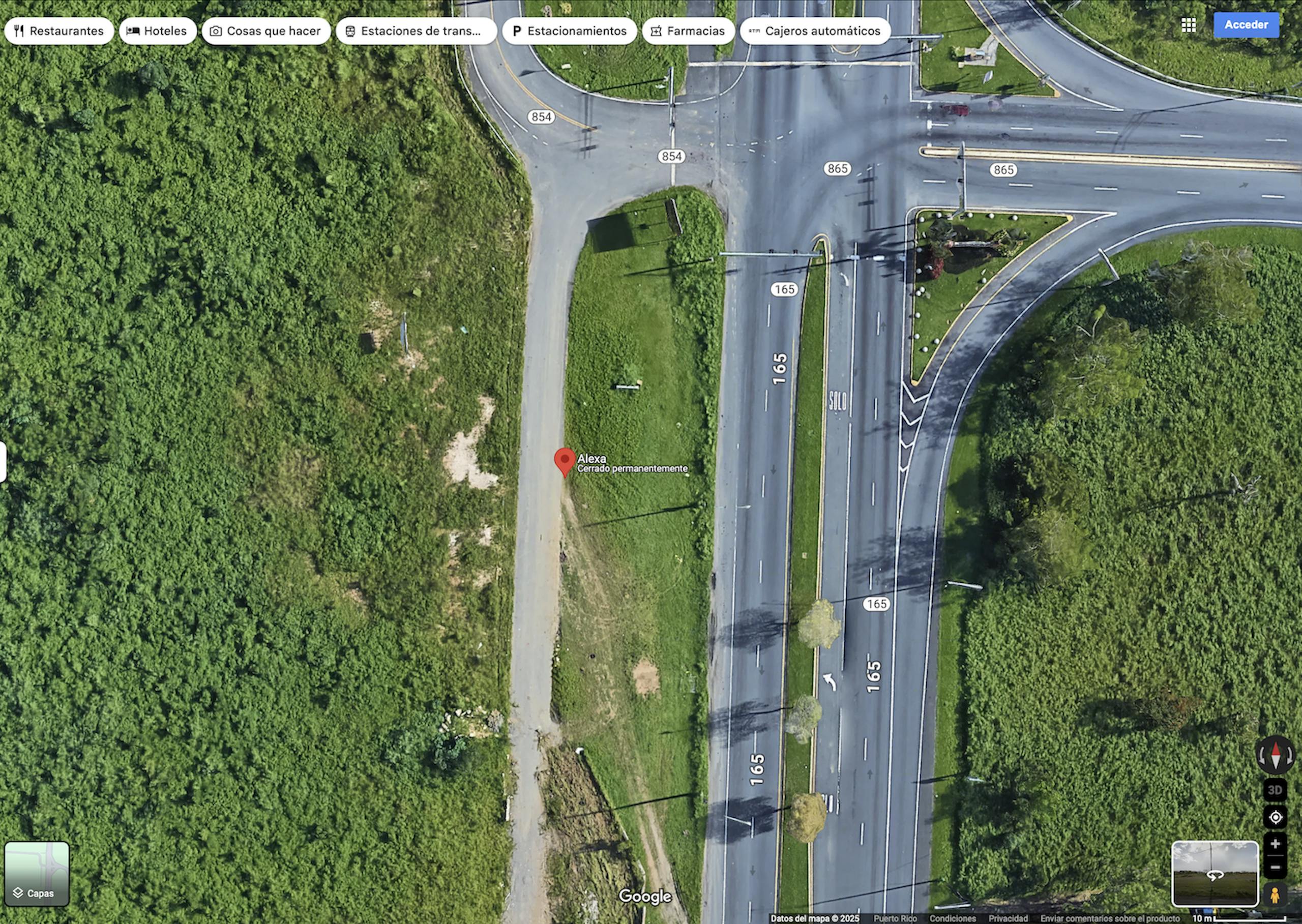

Puerto Rico, International Participation, 24th International Exhibition Inequalities, 2025, photo by DLS Studio

Puerto Rico, International Participation, 24th International Exhibition Inequalities, 2025, photo by DLS Studio

In the second text that I wish to return to, sociologist Bianca Beccalli analyzes the relationship between difference and inequality, taking as an example the difference between genders. Beccalli reconstructs the phases that this concept has passed through in the feminist movements: at the end of the 19th century, the difference between men and women was emphasized, and was considered a diversity to be protected; in the 20th century, however, the value of this difference was relegated to second place, superseded by the search for formal equality, in the workplace, in rights and in political and public representation. In the 1980s, however, gender difference regained its place in feminist discourse, serving as an essential tool in combating the presumed neutrality of the universal Subject.

“This only lasted for a short time, however," Beccalli argues, "since the critical impulse against general explanation, the practice of ‘deconstruction’, the focus on studying the specific and the different, undermined that appeal to difference that had been emerging in the 1980s almost as a new essentialism: nowadays, feminist research describes the many different stories of women of different ethnicities, different sexual preferences and different cultures [...] In contrast with the protagonism and schematism of white, educated, heterosexual feminists, the women's movement has refocused attention on the different stories of black and Hispanic women, descendants of slaves, lesbians, and women who are diverse in a variety of ways, through the interweaving of race, class and historical events."

Shapes of Inequalities, 24th International Exhibition Inequalties, 2025, photo by DLS Studio

If Beccalli initially affirms that “we are not different because we have more or less of the same commodities, but because we are different”, it later becomes clear that “some differences also correspond to inequalities”, and this remains true today. Difference in gender, for example, continues to create inequalities and Federica Fragapane's installation for Inequalities states some unequivocal facts: unpaid care workers are still mainly women, who devote five hours a day to care work on average, compared to the two hours that men devote to it; women earn less for the same job, and only just over half of women have their own personal bank account.

One of the maps curated by Maurizio Molinari also shows the strong global imbalance in political representation: most countries are still governed by men. As Beccalli points out, within gender discrimination there exist other forms of oppression linked to ethnicity, class, sexual orientation or gender identity. The Puerto Rico pavilion offers an example, describing the murder of a homeless black trans woman, the victim of a violence that interweaves various interconnected lines of discrimination; finally, Fragapane's data also show that in the USA, the risk of pregnancy-related death is higher for black women, native Americans or indigenous Alaskans.

Atlas of a changing world, 24th International Exhibition Inequalities, 2025, photo by DLS Studio

In the face of these data on inequalities, we naturally ask ourselves what can be done and how we should respond when it is the system itself that produces injustice. De Solà-Morales answers this question by outlining three possible responses: submission, that is, passive acceptance; delinquency, or purposeless destruction; and finally resistance, which he himself indicates as the preferable way to respond, developing the idea of “an architecture of resistance”, capable of striking the system from within. Indeed, De Solà-Morales suggests:

We need to go back to the myth of Odysseus and Polyphemus

“We need to go back to the myth of Odysseus and Polyphemus: from inside the cave, from inside the power network, we need to sense the escape routes, to guess where the cracks are. Then we need to develop strategies, violent acts that open up gaps, create stoppages, reinforce differences and cause breakdowns. The military machinery in the art of resistance is often rudimentary and marginal, like the burning stick that Odysseus brandishes. We need to exploit the temporary sleeping of the giant to attack him in his weakest point, the eye, which represents, in an image of poetic brilliance, the very essence of control.”